Yachting through the Greek Islands Offers Seas, Scenery and Serenity

Crowds may be fine at football games, Olympic events and yard sales. But when it comes to vacations, some of us crave getaways that truly get us away.

For me, an ideal escape involves a clutch of friends, a teak-decked boat and a sea garnished with picturesque islands. It’s all the better if the isles are Greek, the vessel a chartered yacht and the six chums I share it with promise not to hog the ouzo. Even Aristotle Onassis could not have asked for more.

Fortunately, one does not need Jackie O’s inheritance to rent a crewed yacht. With vessels starting around $5,000 per week, a group of cost-splitting friends can charter a craft for the price of a decent cruise. Granted, the cabins may be more cramped and shuffleboard courts absent, but these amenities pale against the freedom of experiencing the sea unencumbered by fixed itineraries.

We sail from Rhodes, largest of 12 islands in Greece’s Dodecanese chain located near the coast of Turkey. Its major city, also called Rhodes, rose as a Bronze Age kingdom. It became a Greco-Roman art center, and retreating Crusaders made it a fortified stronghold. The city ultimately fell to T-shirt vendors in the 20th century.

Our vessel awaits outside Rhodes’ Old Town, a city-fortress the Knights of St. John began in the early 1300s. Ponderous walls made from cut rock line cobblestone streets. Arched causeways link stone facades, thick doors fill Gothic portals and turrets tower skyward. I feel humbled by the site’s medieval power.

I also feel crushed by crowds. Waves of tourists chatter in a Berlitz sampler of languages as they follow guides lofting colored pennants. They haggle with merchants hawking wares from sidewalk shops. They queue into columns awaiting entry to the Palace of the Grand Masters. Like a salmon in a spawning run, I become trapped in the onslaught. The boat offers an escape.

The Carmen Fontana lies moored next to the Sultan of Oman’s yacht. Our more humble craft has five cabins with beds for ten. Its refrigerator holds the beverage supply, a topside deck provides a sunning retreat, and crewmen stand ready to serve meals onboard. The captain fires the engines, and waving good-bye to an unseen Sultan, we motor into the Aegean.

A few hours later, we anchor at Lindos, midway down the island’s eastern shore. Bluffs tower over a community skirted in whitewashed houses. Below lies a crescent of sand covered with umbrellas in such uniform rows, it looks like a military parasol parade. If the orderly Swiss had an ocean, this is what their beaches might look like.

Cars are banned from the hillside village. To reach the cliff-capping acropolis, visitors either walk or ride donkeys. Choosing beast over brawn, I hop into a saddle hard enough to bruise even Zorba’s ample padding.

A quiet breeze brushes the summit where Alexander the Great, Helen of Troy and Hercules supposedly once stood. Columns from bygone eras point skyward. Below, narrow streets wind past homes and shops where merchants quietly await business. People sit at outdoor tavernas savoring views with a brew. Carfree and carefree, Lindos offers a serenity absent in the town of Rhodes.

Peals from the town’s bell tells us it’s late, and we need to return to our craft. A three-hour voyage separates us from our next island. The motion of the ocean rocks me to sleep on the journey over.

“Sea travel affects the thyroid differently in each sex,” theorizes my Italian-born friend Roberto Mitrotti. “It makes men more relaxed, which is why they love to sail. Women, on the other hand, get amorous,” he adds, winking at his young American girlfriend. “That’s why they love to sail.”

We dock in Symi, the main village on the island of the same name. Twelve feet from our stern, workmen sit at a taverna drinking beer. If we were any closer, the waiters could offer table service. We dine on the deck, much to the delight of staring locals.

In the morning I go for a walk. Although popular, Symi seems less touristy than Lindos. Two-story pastel homes, once the residences of sponge merchants, round its waterfront. Behind, desert mountains rise toward unblemished skies. Roosters crow, chickens peck and children play while mothers watch. Men ride motorcycles and women scoot by on Vespas. Cars and trucks are few. Tranquility prevails.

Small fishing boats bob in a shallow harbor. Each looks like it was colored with the brightest crayons a child could find. The transparent water shimmers in shades of teal and turquoise. Beyond spreads a sea as blue as unwashed Levi’s. It’s like I’m walking through a virtual tourism brochure.

Our captain, Tasos Dimisetis, joins us for a late lunch. He says he has spent almost 27 years at sea. He was a cargo-ship officer for six and served as a cruise-ship master for another six. Since then, he has captained yachts. When he’s not sailing, he hunts wild boars.

“This guy’s truly a man’s man,” jokes musician Iris Brooks.

After lunch, we sail to Panormitis on the south side of the island where we visit the monastery of Archangel Michael, patron saint of Greek mariners. A pilgrimage to the sprawling enclave is a ritual for Orthodox sailors. Abbot Gabriel shows us the facilities.

“I have been here 54 years,” the black-robed man says in slow but precise English. “I came after the war.”

He tells us that when the Italians held the Dodecanese during World War II, one of their ships carried both military officers and civilians, including Gabriel. An Allied submarine torpedoed the vessel. Cast to the water, the young man prayed for St. Michael to save him. Six hours later, rescuers arrived. In mortal gratitude, Gabriel dedicated his life to the patron saint of Symi.

A grandmotherly woman serves us cookies and glasses of fig schnapps, a monastery specialty. As we depart, I hear Gregorian chants coming from the chapel. Perhaps it’s the alcohol, but I suddenly feel touched by an archangel.

Yacht life falls into a pleasant routine. We spend the days exploring. Come evening, we nap while the captain sails to new shores. Then it’s time to rise and dine.

At midnight we arrive at Nisyros, a volcanic isle northwest of Rhodes. After docking in the capital of Mandraki, we follow lights to an open-air taverna where late-dining patrons engage in lively conversations. A waiter approaches.

“Do you want your fish cleaned or uncleaned?” he asks. “You know, with the insides still inside?” Considering the options, I choose pork.

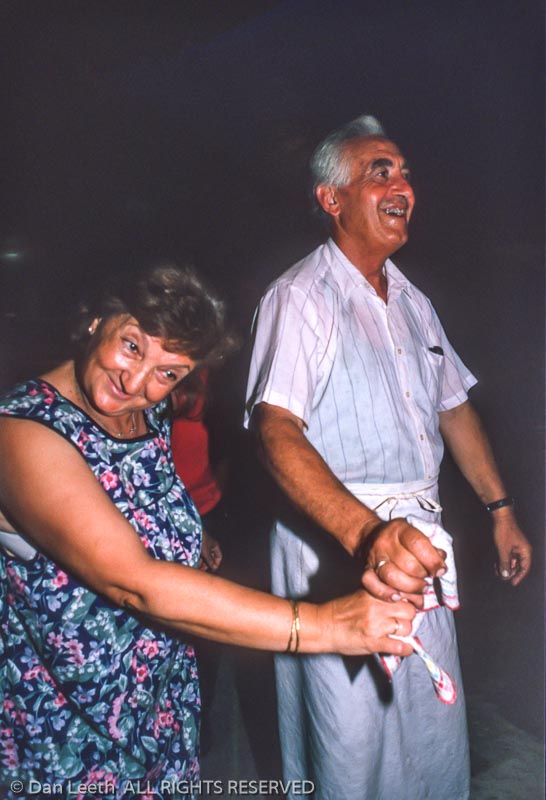

At 1:30 in the morning, dancing starts. The chef and the owner’s wife perform a traditional handkerchief dance, substituting dishcloths for hankies. The festivities continue at the island discotheque.

Rising at the crack of noon, the seven of us stumble out for a van tour of the island. We motor up slopes terraced with rock walls and dotted with oak and olive trees. At the top lies Nikia, a hilltop village perched on the crater rim. Its whitewashed buildings sport royal blue doors, shutters and trim. The incense of cook-stove smoke melds with the potpourri of blossoming flowers. Stairs and walkways wind in a maze of routes. It’s the classic Greek Island cliché of stucco and bougainvillea, only here we enjoy it free of shop-swarming cruise commandos.

“There are only about 40 inhabitants left in this village,” says guide Vera Sakka. “Most Niserians have emigrated to Rhodes, Athens or even the United States and Australia. But I stay. I like to open my eyes with a smile.”

Back onboard, we enjoy the advantage of private yachting and vote to overnight again in Nisyros rather than move on. In the disco, the town’s mayor shows up to try convincing us “rich foreigners” into investing in local tourist development. Bailing on the business talk, I walk back to the boat and sit alone on the deck. The night is dark and dead quiet. It’s an eerie silence seldom found in my urban world.

As we sail away in the morning, I watch Nisyros disappear into a blur of blue sky and bluer water. I’m glad I was able to see the island before multitudes overrun its shores and strangle its allure.

We head to the island of Chalki. Now home to only a handful of residents, it was once prosperous with a population of 4,000. Copper came from its hills and sponges from its waters, but the mines played out and the divers moved to Florida. Then the sea infiltrated the water table, making the once fertile landscape barren. Fresh water now arrives by tanker.

Neoclassical homes line the harbor. In their midst rises the wedding-cake tiers of a church bell-tower. Fishing boats in a rainbow of vivid hues float on water clear as a mountain lake. Their owners work on untangling nets. A quarter-mile away lies the town’s beach where neither umbrellas nor vendors mar the sand.

“My wife and I come here to do nothing,” says Chris Heather, on holiday from England. “It’s a different life. Anything important you must bring with you because there are no shops, no movies, nothing at all.”

Wading the surf, I feel content. The crowded, chaotic world of home has dropped into a distant memory. It’s as if I have been sedated for a week, living a halcyon dream of rest, relaxation and renewal.

Isn’t that what vacations are for?