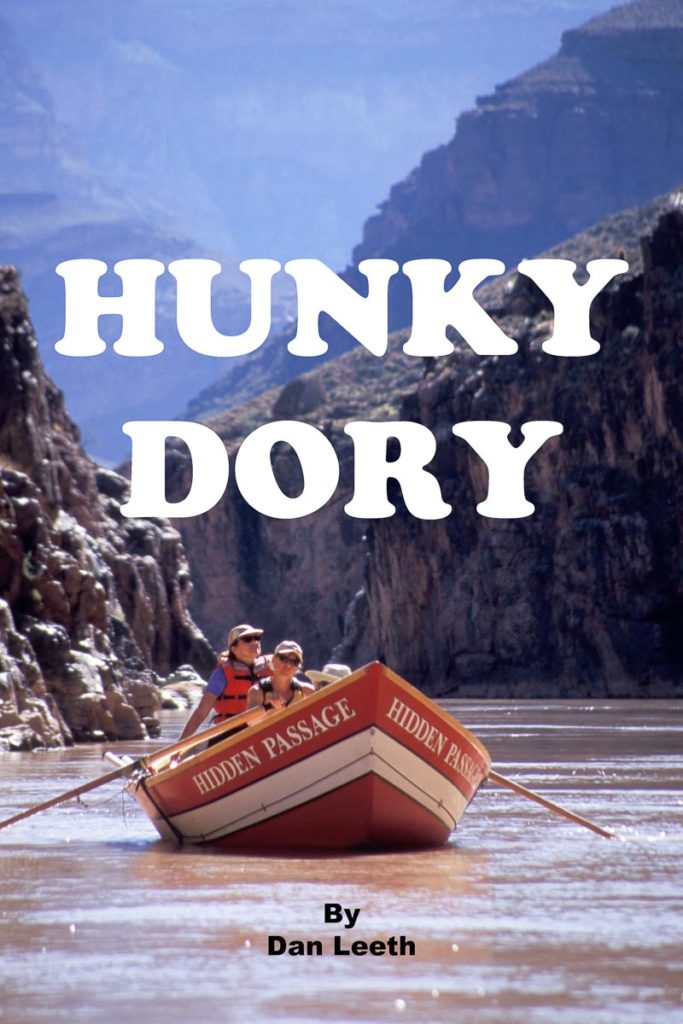

The Most Exciting Way to Experience the Grand Canyon May be in a Wooden Boat

Like a liquid freight train that’s jumped its tracks, the entire flow of the Colorado River careens toward the canyon’s far wall. Beyond, it shakes and churns down a channel choked with submerged boulders. Between those rocks and the hard place froths enough hydrological mayhem to flip the Queen Mary.

Expedition leader Bill Bruchak guides our tiny boat toward the left side of the flow. With a series of hefty pulls, he rows stern-first into the agitated bedlam. Engulfed in turbulence, Bruchak yanks an oar, and we pirouette to go with the current.

Ahead stands a wave taller than a suburban tract home. As we graze its side, water arcs down, filling the foot wells 15 inches deep. A series of rolling tail waves follow. Like the mechanical bull at Gilley’s, the boat bucks through each swell with all onboard screaming “HEE-HAW!”

We finally reach the eddy at cataract’s end, and I’m beaming. House Rock Rapid has just given me an exhilarating taste of how dories cruise through white water.

The sports cars of commercial river running, dories are made from wood, foam and fiberglass. They stand about 18 feet long, 56 inches wide and comfortably hold four passengers and an oarsman. A flat bottom and upturned ends make them easy to steer on the river, and because they have rigid hulls, they don’t flex with the waves as rubber rafts will. Instead, a sharp prow splits the water in a way that makes even riffles exciting. Unlike inflatables, however, these rigid-walled craft can crack on rocks, so dory drivers must carefully plot routes through rapids.

“They’re a royal pain sometimes, but they’re worth it because of the ride you get,” says guide Shawn Browning.

On this Grand Canyon Dories journey through the length of the canyon, we have four boats for 16 clients, rowed by a three-man, one-woman crew of seasoned guides. The bulk of our gear travels onboard a pair of oar-powered baggage rafts.

Our first camp lies on a riverside beach two miles below the rapid. In a drill that’s repeated for 17 nights, everyone first unloads gear and waterproof “dry bags” from the rafts. While we seek sleeping sites, the cooking team begins preparing a fresh-food dinner in a portable kitchen, complete with propane stove and lantern. The boatmen assemble water-purification and hand-washing stations, then find a secluded yet scenic spot for the portable potty. Nicknamed “The Unit,” this toilet-seat-on-an-ammo-can offers a throne with a view.

We spend evenings circled around a campfire. The Milky Way shimmers overhead, its luminescence painting the gaps between inky canyon walls. Civilization fades far away.

Most mornings, I awaken to the descending notes of a canyon wren. After coffee and a hot breakfast, we load boats and head downstream. Calm current and raging white water await.

Rapids occur near the mouths of side canyons where flashfloods have washed rocks and rolled boulders into the river. We porpoise through most like dolphins on pep pills. If the boat hits waves straight on, the prow shoots high into the air with nothing but blue above the bow.

Grand Canyon cataracts are rated on a 10-point technical scale, with “one” being a dancing riffle and “10” a slobbering ogre ready to devour anything floating through. I soon develop my own “fun-factor” rating system based on how many inches of water occupy the foot well at rapid’s end.

Although pros operate the oars, dory passengers play a part in running rapids. We are responsible for “high siding,” a weight-shifting maneuver that helps keep the boats from tipping.

“If a big wave’s coming right at the side of the boat, you want to lean into it,” says guide Elena Kirschner. “That means you’re going to get wet and cold, but it’s a lot less wet and cold than swimming in the river.”

Fortunately, dories seldom flip, and unlike rafts, they are easy to turn right-side up. None of ours tip over, but a private raft trip that launched the same day we did experiences several upsets.

“There’ve been some deaths on the river by drowning and being hit,” says Martin Litton, the man who introduced dories to the canyon. “Nearly all of them have occurred in inflatable rafts.”

In 1869, Major John Wesley Powell led the canyon’s first float trip in wooden boats. Built for straight-line speed, his craft proved unwieldy in rapids. Other river runners followed, each generation improving its predecessor’s designs. It took almost a century for dories to reach the canyon.

“I’d seen these McKenzie boats in Oregon made out of plywood,” explains Litton. “We got a builder to craft a couple of hulls, and in 1962 we made the first trip in dories.”

Litton soon began annual river-running vacations, taking along friends, friends of friends and people he’d never seen before. To keep from going broke, he started charging $180 for his 21-day trips. In late 1968, he quit his senior editor job at Sunset magazine.

“I just walked out,” he says. “From then on, I was in the business of running river trips.”

His company, Grand Canyon Dories, became a leader in the burgeoning industry of white-water river running. In the late 1980s, Litton sold the operation to O.A.R.S., which continues to offer a full schedule of trips.

If rapids provide the river’s caffeine, flat stretches are its herbal tea. In the calm between the cataracts, we relax as oars stroke the water in metronome rhythm. Great blue herons stand by the shore watching our passage. Bighorn sheep gaze down from above. Rock walls reach upward, their colors and textures revealing the canyon’s geological history. We float through nature’s gallery, displayed at its artistic best.

“If this was all flat water, I’d like it just as much,” admits baggage-boat oarsman Kurt Brooks.

Although we stop at the canyon’s famous spots, it’s not the guidebook highlights that prove most memorable. It’s the secret places. We climb to overlooks and hike side canyons to waterfall grottos. We see where geologic faults have bent rock as if it was made of taffy. We examine prehistoric petroglyphs, pictographs and Indian ruins, as well as remains left by miners, railroad surveyors and would-be dam builders.

Conventional civilization lies in abeyance. Only on day eight when we reach Phantom Ranch, an inner-canyon lodge, is our wilderness interrupted. There, surrounded by hikers and mule riders, we buy lemonade, T-shirts and postcards. Escaping back into the wild, we camp for the night below Horn Creek Rapid, one of the canyon’s more challenging cataracts. The worst lie ahead.

The next day, we cover what Bruchak claims is “the biggest navigable water for a dory in North America.” In 23 miles we navigate 16 named rapids that include several of the canyon’s gnarliest. I ride with Browning.

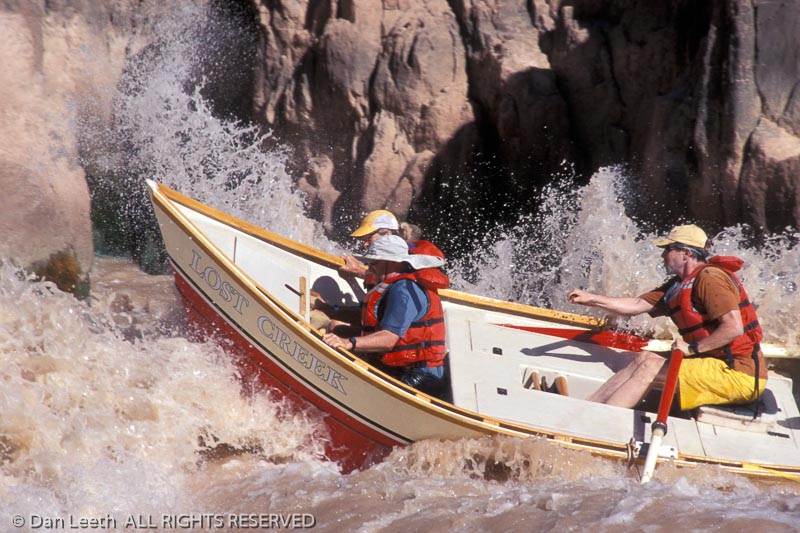

After breezing through Salt Creek Rapid, we hit Granite, a boiling pot of froth and turbulence. Browning aims down the tongue, but misses the line by a few inches. Nipping “the crasher,” he spins around. Suddenly, we’re rushing stern-first toward a very hard wall.

“Schist!” I shout, naming the rock strata lying dead ahead.

Browning pulls the oars with every adrenaline-packed ounce of energy he can muster. But the river is stronger.

WHAM! We hit with an impact that would make a demolition derby driver wince. The collision spins us again so we’re now moving forward. Browning catches the current, and we finally jolt out the bottom of the rapid. Opening the stern hatch, I expect to see a Titanic-size hole, but it’s dry. We’re only bruised, not busted.

“Yikes, that was close,” Browning says in what may be the understatement of the day.

Downstream, we ride Hermit’s 35-foot-tall wave train without incident. After an inconsequential run through Boucher, we arrive at Crystal. Once, this was little more than a riffle, but a 1966 flashflood choked the river with debris, forming one of the canyon’s most gut wrenching cataracts.

“At high water, Crystal is a difficult rapid with dire consequences if you blow it,” says Browning. “We’re at medium-low water, so we’re going to do what is called the left run. It’s big.”

We pull into the current, nipping the edge of a gaping hole. Water crashes down. Like Niagara Falls hitting a teacup, the boat fills from gunwale-to-gunwale rendering it too heavy to maneuver. Boat-shredding boulders loom below.

“BAIL!” Browning cries. “BAIL! BAIL!”

We begin madly flinging water over the sides. Our compatriots say it looks like hoses spraying from a fireboat. We lighten the craft enough to safely negotiate the final white water. At the bottom, we mercifully say our ABCs – Alive Below Crystal.

After lunch, we plow through a succession of cataracts, missing walls, rocks and holes. It’s a repetitive cycle of anticipation and anxiety followed by jubilation and relief. If the dories are sports cars, this is their Le Mans.

I fall asleep, confident that our spunky guides and spritely craft can handle anything the canyon throws at it. That’s good, because the most feared rapid lies three days downstream.

Once, molten magma dammed the Colorado, but the relentless river eroded away the impediment, leaving only a surging drop called Lava Falls in its wake. While not the most technically upsetting rapid, it’s the one that drives more boatmen to hit the Maalox.

“Every time I make that turn and hear the roar, my heart jumps 15 beats faster,” says Bruchak, with whom I ride today.

The cataract looks like a blender churning milkshakes in the river. We slowly approach the lip of the cataclysm like condemned prisoners on a gurney.

“Hang on,” he says. “We’re getting close. Get ready!”

We teeter at the brink, then swoop into the Cuisinart chaos. A ledge to the left has formed a gaping maw in the river. Bruchak pulls the dory to the edge of it, gaining momentum.

“Get ready! Big one!”

We sever a lateral wave and slice down to where two currents rush together to form a bulging V-wave. The bow rises. Water flies. We bounce like an ice cube in a martini shaker.

“Bigger one coming! Hang on! BIGGER ONE.”

We plow through a second, larger V-wave. Torrents crash by the boat’s bow. I grip the gunwales so tightly, I expect to leave indentations in the hardwood. We bound, bounce and bash through the rapid’s gut, finally exiting through the tail waves.

Nine seconds after it began, it’s over. Bruchak pulls into the eddy and everyone breathes a triumphant sigh of relief.

“There’s no place on the river like that,” he exclaims, grinning.

I look at the bottom of the boat. Only four inches of water slosh in the foot well. Maybe Lava Falls isn’t so bad after all.