Today’s hike got off to a bit of a rocky start.

We pulled into the Devils Canyon parking lot for our hike. I hate door dings, so I try to park at the far end of parking lots and stay more than an open-door’s width away from other cars. I backed the truck in a good five feet away from a Toyota Prius parked there.

I thought the car was empty, but as it turns out, there was a man sitting in it. As we got out, he rolled down his window, angrily told us we’d parked too close to him. He then insulted us, accusing us of being Democrats.

In the past, I’ve been accused of being born out of wedlock, being the male offspring of a female dog and of having an incestuous relationship with my mother. To this guy, maybe being a Democrat is worse than any of those. Sorry, fella, but we don’t qualify.

Rather than risk possible retaliatory vandalism, we drove on and parked at the Fruita Paleontological Area parking lot, where we avoided parking near any car bearing a Trump or Lauren Boebert bumper sticker.

Fruita is famed for its dinosaur discoveries. They began in the early 1900s when a paleontologist from Chicago’s Field Museum dug into a nearby hillside and unearthed nearly 2/3 of the fossilized remains of a Brontosaurus. Today the famed Dinosaur Journey Museum lies across the street from our RV park in Fruita, and to celebrate Christmas, the Grinch rides high in the jaws of Fruita’s giant dinosaur replica.

From our Paleontological Area trailhead, a one-mile, education loop trail lies dotted with interpretative signs providing more information than I want to know about these ancient lizards. An alternative trail from there leads to the Skinner Cabin and beyond. We opted for the cabin route.

The Skinner Cabin was apparently built around 1905-10 by a stonemason named John Skinner who owned a ranch on the other side of the river. In the 1940-50’s, it was occupied by John Condon, a man who made part of his living by digging up and selling dinosaur bones. The cabin was abandoned in 1953 and had pretty much fallen into total disrepair by 2016 when volunteers began restoring it to its original configuration. A wooden rail fence now encourages people to stay out, and other than a bit of interior graffiti, it seems to be working.

From Skinner Cabin, we continued down the trail to the Devils-Flume Connector Trail, which we had hiked on Wednesday. I wanted to continue on and explore the bottom of the box canyon we had admired then from above. Map in hand, we somehow took all the right trail junctions to reach the D4 Loop Trail that would take us into that canyon.

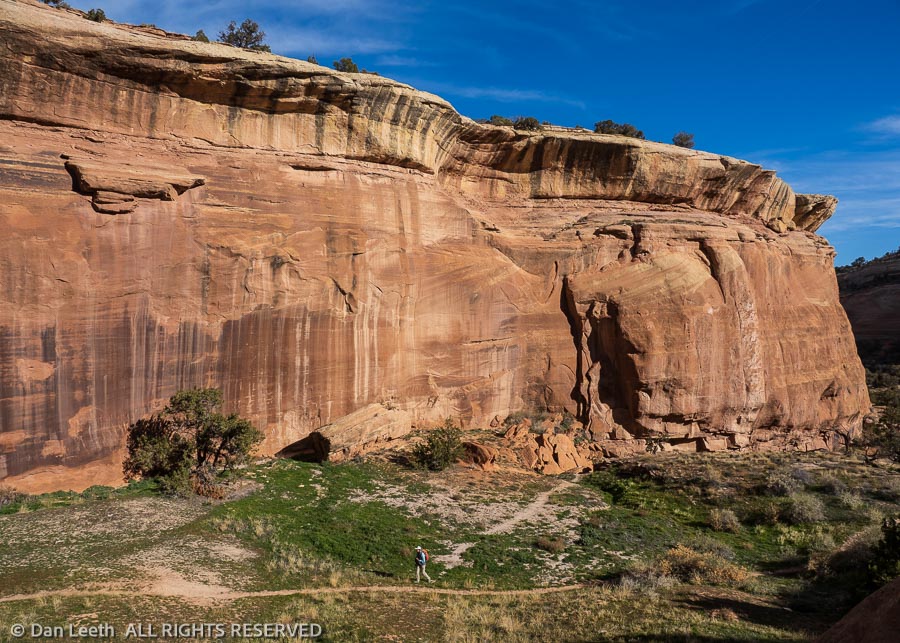

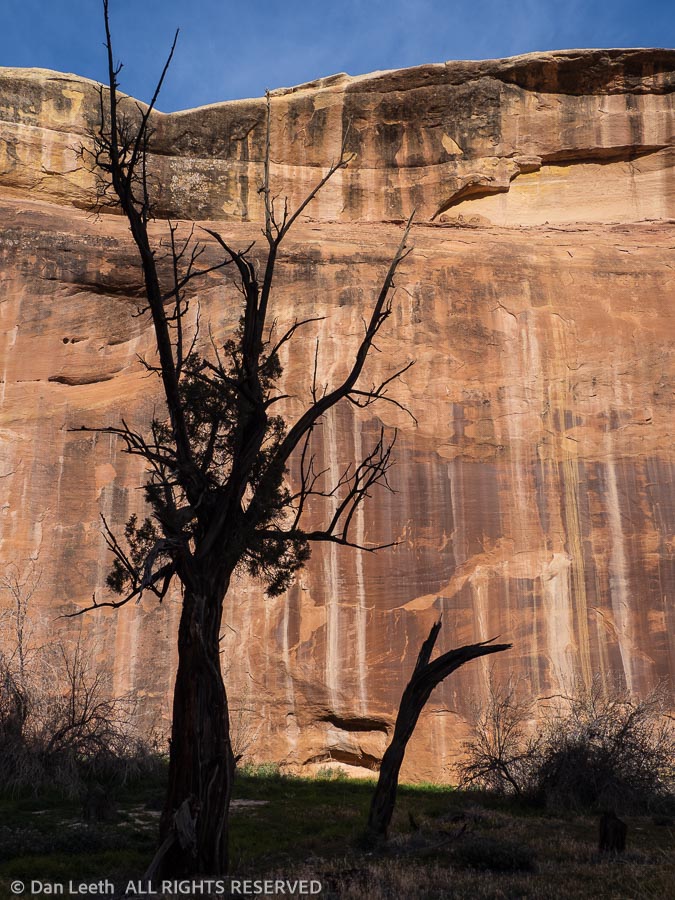

From the first time I read the Sierra Club coffee table book “Slickrock,” I’ve been enamored with the sandstone-walled canyons. Hiking this short canyon was a treat. Even at high noon, the low, pre-solstice sun made the sandstone cliffs blush. Streaks of desert vanish draped those towering walls, and the trunks of living and dead junipers offered inspiring silhouettes against the vivid, stony backdrop.

Reaching canyon’s end, we looked up. Using just the friction of our boots on the slickrock (which actually has the texture of sandpaper) we figured we might make it maybe halfway to the top of the canyon-ending pouroff. Beyond that, it looked impossibly challenging with the emphasis on “impossible.” Lacking Spider-Man’s agility, we turned around and headed back.

Returning toward the Skinner Cabin and our nonpolitically parked truck, we found the remains of some cement water headers and a few six-inch, PVC pipes poking from the ground. In the 1990s, the area around Devils Canyon was privately owned and slated to become an upper-end housing subdivision complete with a golf course. Thankfully, the BLM bought up the land before those plans became irreversibly implemented.

“Those must be the golf course sand traps,” my wife joked as we passed patches of white sand garnishing the nearby desert floor.