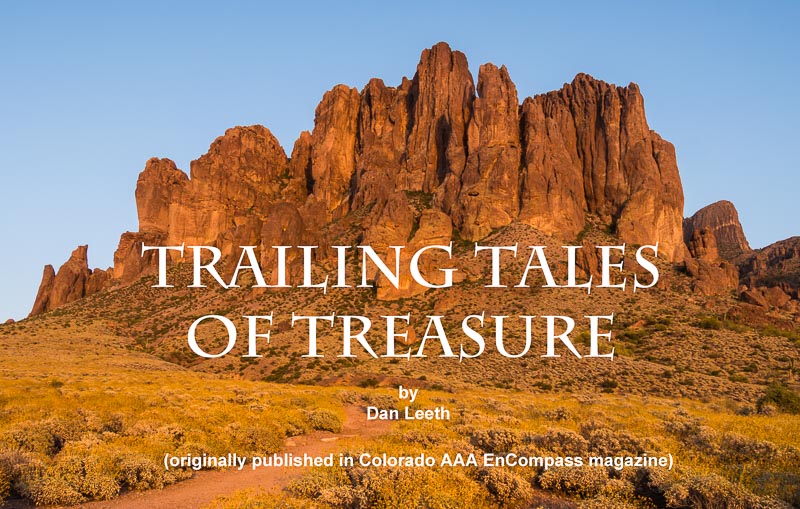

Arizona’s Superstition Mountains Lie Laced with the Legends of Lost Lodes

It was my first ever hike. I was nine years old when my father’s friend, Scotty, invited us to join him on a trek into the Superstition Mountains, a rugged jumble of bluffs, buttes, crags, cliffs and canyons rising 35 miles east of Phoenix. Naturally, I wore my Roy Rogers cowboy boots. Six blisters later, I realized why Roy rode and seldom walked. Only Scotty’s tales of treasure kept me going.

As every Arizona kid of my era knew, the Superstitions held the Lost Dutchman Mine, and Scotty was an expert on this missing treasure trove. He led us into an area known as the Massacre Grounds where the story got its start.

According to Scotty, the Peralta family from Mexico opened 18 mines in the Superstitions from which they extracted gold in unbelievable quantities. Their last foray, a procession of 400 men and 200 pack mules, came in 1847. On their return, they were ambushed, their gold was scattered and their mines were soon covered over. Skeletons, rotten saddlebags and $18,000 in loose, gold-veined concentrates found later in the area support the story’s accuracy.

The only thing we discovered on our adventure was an arrowhead and a shallow cave whose campfire-sooted walls stood black as a chalkboard. Somebody spent many nights camped here. I figured it was the Dutchman.

As the story goes, two German prospectors, Jacob Waltz and Jacob Wieser, drifted into a small Mexican village where they rescued a man from a barroom brawl. In gratitude, the saved señor, a Peralta relative, gave the partners a map and ultimately rights to the family’s Arizona diggings. The two Germans headed north, and in a land so rugged that even a lizard could get lost, they found the Peralta site left uncovered. It held, according to Waltz, an 18-inch vein of pure gold.

“World’s richest mine,” he bragged.

Wieser’s good fortune remained short lived. With Waltz allegedly out buying supplies, someone murdered Wieser. All the gold now belonged to the “Dutchman,” whose nickname either came from Deutsch, the German word for German, or his contemporaries bore a worse sense of geography than today’s sixth-graders.

I’ve logged hundreds of trail miles in the Superstitions since that first experience. Today, I’m introducing my wife, Dianne, to the area. As Scotty did for me, I’m sharing with her tales of the Dutchman and the “Dutch hunters” who followed.

Our springtime hike from the First Water Trailhead begins, appropriately, on a trail named for the Dutchman. The cool morning air carries the fragrance of wildflowers. Mourning doves coo plaintive dirges in the distance.

Although historical records cannot confirm Wieser’s or the mine’s existence, Waltz was a very real person. Born in Germany, he immigrated to the U.S. in 1839. A decade later, he headed west for the California gold rush, obtaining American citizenship in Los Angeles. He later moved to Prescott, Arizona, where he filed mining claims.

In his snow-bearded years, Waltz settled down in Phoenix to raise chickens on a 160-acre plot near the Salt River. The stream flooded in 1891, and Waltz spent two frigid nights in a tree before being rescued. He contracted pneumonia from the incident.

Julia Thomas, a German-speaking ice-cream parlor owner, cared for the ailing Dutchman. After eight months’ convalescence, the 81-year-old Waltz took a turn for the worse. Prior to cashing in, the Dutchman attempted to disclose his mine’s whereabouts, but all he ended up bequeathing were vague directions and a few pounds of gold-laced rock.

Firmly believing she could find his mine, Thomas sold her shop and rode into the Superstitions the following August. Waltz’s deathbed instructions ultimately proved impossible to follow. After repeated searches, Thomas did the next best thing. She sold maps to the mine she couldn’t find.

Our trail parallels First Water Creek as it whispers through rock-lined pools. Come summer, the creek will be deathly dry. I know because like Julia Thomas and a slew of other Dutch hunters, I’ve hiked here in the height of heat.

Years ago, a group of us wanted to see what it would be like to explore the wilderness when temperatures topped triple digits. It wasn’t fun. By the time we reached our campsite, we were sizzling like pigs at a luau. We spent the remainder of the day simmering away beneath a cottonwood tree.

Dianne and I cross Parker Pass and head down to Boulder Basin, an open area studded with cactus and laced with wildflowers. A short detour up East Boulder Creek takes us to the site of Aylor’s Caballo Camp.

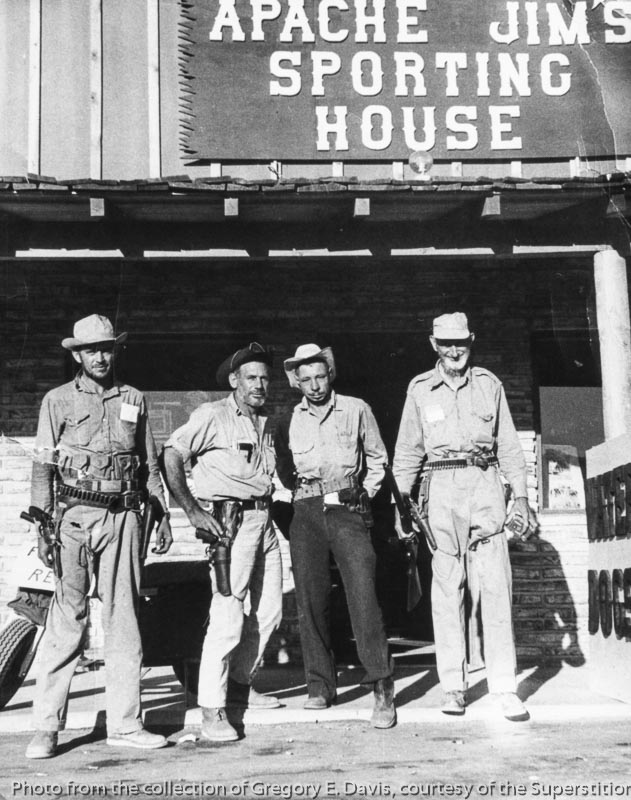

Arriving from Colorado, Chuck and Peg Aylor moved into the Superstitions in 1939 hoping to find the Dutchman’s lost diggings. They remained here until the Forest Service evicted them in the 1960s and dismantled their camp. Although the Aylors found nothing of value, they at least left alive. Many were not so lucky. One of the most famous of the dearly departed was Adolph Ruth.

A retired bureaucrat from Washington, D.C., Adolph Ruth came in 1931 with an old map his son had obtained from a Mexican diplomat. He arrived in mid-June and immediately hired a couple of cowboys to pack him into the Superstitions. A week later, a rancher found his camp empty. Ruth was nowhere to be seen.

A 45-day search ensued with no results. Six months later, members of an archeology expedition found a skull several canyons away, which authorities confirmed was Ruth’s. Bullet holes punctured both sides of the cranium.

The rest of his skeleton and personal effects turned up a half-mile away. In one pocket was a sheet of paper on which Ruth had written “Veni, Vidi, Vici” (I came, I saw, I conquered). His map was missing.

Dianne and I continue our hike over Bull Pass and down into Needle Canyon. A buzzard circles overhead, perhaps hoping that we, too, are doomed Dutch hunters. We aim to disappoint.

Weavers Needle, icon of the Superstitions, towers to the south. In the shadow of this thousand-foot-high volcanic monolith, two rival groups battled in the 1950s over lost gold, but not from a mine. They sought a treasure allegedly stashed by priests.

After King Carlos III evicted the Jesuits from New Spain in 1767, a missionary-led pack train supposedly entered the Superstitions with 240 heavily burdened mules. When the convoy reemerged, the animals bore no loads. The toted treasure, the opposing factions figured, must be hidden in these hills.

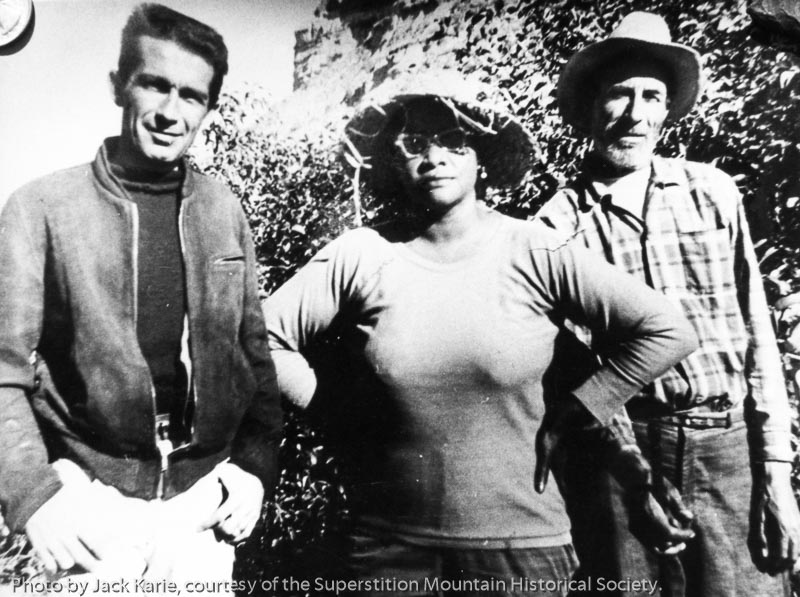

One heavily armed band was led by Celeste Jones, a black woman who claimed to have studied music at Juilliard and sung with the Metropolitan Opera. She traipsed about the mountains in sneakers, Bermuda shorts, sunglasses and a wide-brimmed hat. Jones believed gold lay hidden in Weavers Needle, guarded by a band of people visible only to her. To win their favor, she serenaded them.

Ed Piper, a lanky white prospector, led the opposing armed camp. He generally donned khaki trousers and, like Jones, always sported a sidearm. He was an accomplished farmer and planted fruit trees in the desert near the base of Weavers Needle. Both groups shared the area’s sole water source.

Animosity peaked when Piper killed one of Jones’ men. He was questioned, but for lack of witnesses, the court ruled self-defense. Diagnosed with stomach cancer, Piper left in 1962 and died two months later. Jones stayed another year before departing the Superstitions for good.

We follow Boulder Canyon downstream to the Second Water Trail, our return route to the trailhead. Afternoon light glints off cholla and saguaro needles. Butterflies flutter among purple-flowered thistles, globe mallows add dollops of orange and century plants stalk upward in their single reproductive shot before death.

“Does the mine really exist?” Dianne asks.

Scant documentary evidence exists to support the existence of Dutchman’s diggings. No claim was ever filed, and tax records show Waltz claimed only around $200 in personal property. But folks occasionally lie to assessors, and locals saw Waltz brandishing gold from somewhere.

“I believe there is a Lost Dutchman Mine,” Mike Smith, who formerly managed a local prospecting supply store, once told me. “There are enough facts to conclude something is out there.”

Critics speculate that Waltz may have stolen ore from the Vulture Mine northwest of Phoenix. Others contend the Dutchman’s nuggets came from a mine in Goldfield, four miles north of Apache Junction.

“That was a possibility,” Smith countered, “but Dr. Tom Glover did electron dispersal analysis of ores from Goldfield and the Vulture. None matched the Dutchman’s.”

Longtime Dutch hunter Ron Feldman, owner of Apache Junction’s OK Corral stables, suggested to me that the Dutchman’s mine may already have been totally gutted in the ’20s.

“Think about it,” he argues. “If you found the mine and staked a claim, foes would come right to you. Your best bet would be to keep your mouth shut.”

History may never reveal the truth of the Dutchman’s gold, which is fine by me. The lingering mystery offers a inexhaustible excuse to poke around this inspiring El Dorado. After all, as Scotty pointed out on my first hike years ago, “If failure foiled dreamers, no one would drop a second quarter in a slot machine.”