Whoever invented the sport of skeleton must have suffered from loose bones in the brain.

Take a steel-framed sled that’s about a yard long and inches high. Place it on an ice-plastered, concrete bobsled track with banked corners capable of exerting 5-g centrifugal forces. Push off, and like a bowling ball careening down a laundry chute, slide down headfirst at freeway-worthy speeds.

I can’t wait to try it.

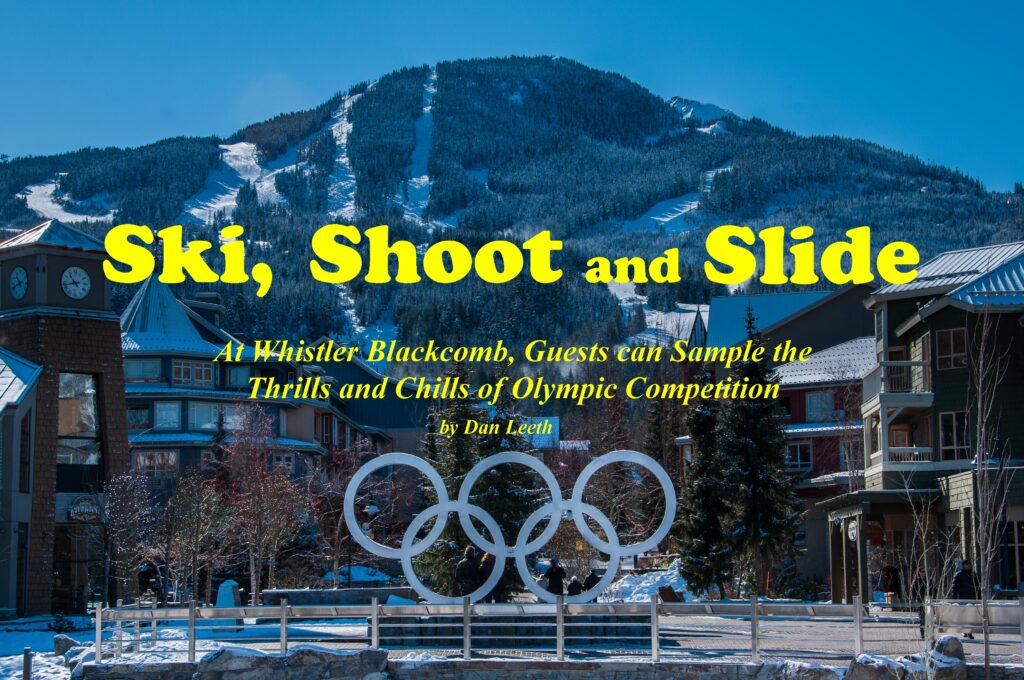

Along with bobsled and biathlon, sampling skeleton is one of the Olympic Legacy Package options offered through the Four Seasons Hotel at British Columbia’s Whistler Blackcomb ski resort.

Home to the 2010 Olympic alpine, Nordic and sliding events, Whistler remains one of North America’s largest single ski area with terrain ranging from groomers to glaciers. It boasts a mile of vertical relief, one of the greatest drops on the continent. I spend my arrival day sliding the slopes like gold-medalist Bode Miller, but at a quarter the speed and a fraction the form.

My first Olympic Legacy event is the Discover Biathlon Experience held at Whistler Olympic Park in Callaghan Valley, a 20-minute drive from the village.

In men’s Olympic competition, instructor Jessica Blenkam explains, cross-country skiers race a four-kilometer course which ends at the shooting range. With hearts pumping at a rate that would send Richard Simmons to the ER, the athletes fire five shots at tiny targets. For every miss, they do a 150-meter penalty lap. They then ski another four-kilometer loop and fire again. In all, they do five loops and four firing sessions – two standing and two prone.

“First, we’re going to do a little bit of a skate ski lesson,” Jessica outlines. “Then we’re going to do some marksmanship.”

While I downhill and have a long history of classic, kick-and-glide cross country skiing, I’ve never skate skied. Jessica shows me how to balance, how to push off, how to pole and how to turn. She does her best to provide positive reinforcement.

“You’re really good at getting up after falling!” she exclaims. “And wow, you still have both your skis on. Good job!”

After an hour spent trying to master skate skiing, it’s time to shoot. At the 30-lane firing range, a mat and rifle await me at station five.

“Those targets are 50 meters away,” Jessica points out. “The standing targets are the size of a grapefruit, and the prone are the size of a plum.”

The rifle is a Russian-made .22 caliber specially built for biathlon with bullets enclosed in five-shot clips. Jessica assures me that it’s very similar to what the athletes use, although theirs would probably have a carbon-fiber stock specially fitted to their bodies and cost thousands of rubles more.

“This is similar to a bolt action, but it’s called a Fortner action,” she explains. “It’s designed to fire accurately and perform well in cold, wet conditions. We’ve zeroed the rifles in so they’re dead accurate.”

Lying on my belly, I center the first circle in the sights. Gently, I squeeze the trigger. The shot echoes, but the target remains black.

I missed.

I fire again. And again. By the time the clip is exhausted, only two targets have turned white. Over the course of the next hour, my best result is four out of five, and I don’t have to ski before firing. Maybe biathlon will not be my podium event.

Back in town, I wander the pedestrian-friendly village, which feels like a huge outdoor shopping mall. Overall, Whistler boasts 9,500 permanent residents and 11,500 second home owners. There are at least 24 hotels and enough timeshares and condos to house more than 30,000 visitors at one time. The area boasts 200+ retail shops, 90+ restaurants and cafes, 30+ bars and lounges and 20+ spas. All fit together in architectural harmony, each painted in its own shade of brown.

“There’s a very specific look and feel that you have to have when you’re opening a business in the resort,” admits tourism official Kerry Duff.

Built in 2004, the Four Seasons is one of Whistler’s newer hotels. It bills itself as a 273-room, rustic modern retreat, and along with the Ritz-Carlton in Toronto, remains one of only two AAA Five-Diamond hotels in all of Canada. Located in Upper Village on the Blackcomb side, it’s not ski-in/ski-out, but they do offer free shuttle service to a slope-hugging ski valet center.

That evening, I hit the Four Seasons Spa and splurge on a heat-therapy treatment originally created for the Olympics. Now called the “Spirit of Whistler,” it began as “On the Podium.”

“When the treatment was created, the spirit at the time was the Olympics,” explains spa director Filipa Batalha.

It’s too bad they changed the name. It might have been the closest I’ll ever get to an Olympic podium.

The next day, I head over to the Whistler Sliding Center, site of the Olympic bobsled, luge and skeleton track. It’s nearly a mile in length, sports a 499-foot drop with an average grade of 10.5%. Its 16 corners culminate with Thunderbird, a nearly 180-degree hairpin turn where sleds and sliders experience maximum speeds and G-forces.

“You’re all going to be active participants in the sport of skeleton today,” Anna Lynch tells us at orientation. “You’re going to reach speeds up to 100 kilometers per hour and experience G-forces several times your body weight.”

She shows us the sleds, which look nothing like the Flexible Flyers of my youth. There’s a cutout at the top where our heads go. Our torsos cover the middle part. Arms go down the side and hands grip handles beside our butts. Knees rest on a plate near the bottom.

“Be like a sack of potatoes,” Anna advises. “If you lift your knees or shoulders, the runners are going to be free to move side to side. That’s when you’re going to be tapping the walls. You want to keep a nice streamlined body position at all times. No chicken wings.”

Unlike Olympians who dive onto moving sleds from the top, we start stationary and descend only the bottom third of the track. Anna gives us our starting order. I’m number eight.

My time comes all too soon. Lying in wait, I’m more nervous than the groom at a shotgun wedding.

“You ready?” the starter asks.

Sack of potatoes. Only 30 seconds of sheer terror.

“Sure,” I gulp.

He pushes and I begin accelerating down the track faster than a nitro-flaming dragster. Through goggles, all I see is a whirring blur of gray ice. Centrifugal force slams my helmet down causing the chin guard to scrape the surface. Instinctively, I lift. The sled weaves and I begin caroming off the walls. I make promises I’ll never keep.

Finally, I fling through Thunderbird and stop on the uphill outrun. Like a pilot walking away from a crash, I feel lucky to be alive.

My time is 32:61. After all 20 participants finish their first runs, I’m in 18th place. With two others worse than me, I’m as ecstatic as a nerd who’s suddenly not the last kid chosen for the team.

Exercising better control on my second run, I cut more than two seconds off my time and shoot through the speed trap a hair under 60 mph. That gives me 14th place.

Maybe skeleton will not be my podium event, either. There’s still the final Olympic Legacy option of bobsledding left to do.