Volunteers Help to Preserve a Uniquely Colorado Slice of Railroad History

“We have to be very aware of traffic at highway grade crossings,” explains senior motorman Larry Spencer. “We don’t look like a train. We don’t sound like a train. People see this coming, and they don’t recognize it as being something on rails.”

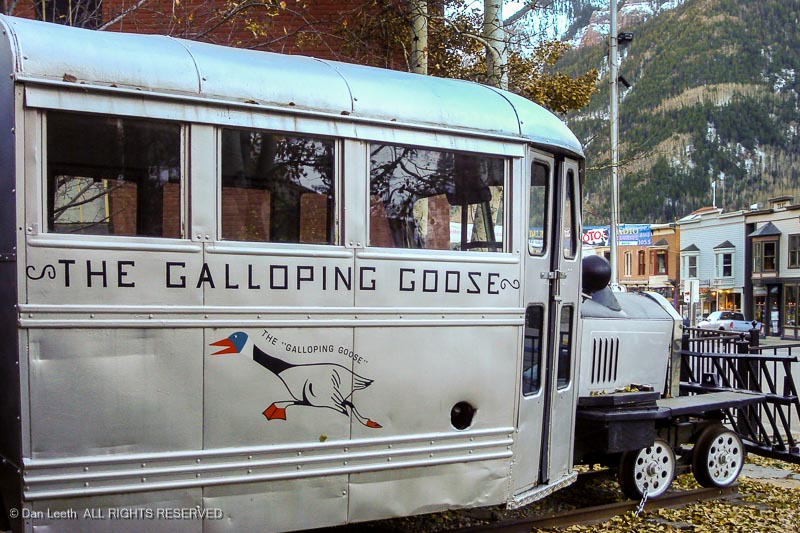

Instead of a smoke-belching locomotive, Spencer and fellow volunteers are driving Galloping Goose #5 – a silvery, rail-running contraption with a vintage auto front-end and a passenger-toting boxcar behind. It’s one of seven such creations cobbled together during the Great Depression to keep the Rio Grande Southern Railroad (RGS) in business.

In the late 1880s, silver gushed from the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado, and miners needed an economical means to haul ore out and supplies in. To that end, Otto Mears, the famed Pathfinder of the San Juans, founded the Rio Grande Southern.

Snaking between Durango and Ridgway, it serviced the mining communities of Rico, Ophir and Telluride. The line, which opened in 1891, immediately proved profitable.

The good times ended two years later with the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Prices plummeted, mines closed, and towns emptied. With little to carry but the mail, RGS precariously hung on.

Then came the stock market crash of 1929. Requiring a minimum of three to four employees to operate, running coal-burning stream trains over the mountains had always been an expensive proposition. With demand further diminishing, the cost of plying the RGS route often exceeded the revenue earned. Needing a cheaper way to conduct business, the railroad hatched their first Galloping Goose.

RGS crews in Ridgway took a 1925 Buick, shortened its cab, extended its frame and bolted a stake-bed platform in back to carry cargo. They installed a swiveling rail-wheel undercarriage in front and flanged drive wheels in back. Goose #1 hit the tracks in June 1931.

Burning cheap gasoline and requiring only one employee to operate, it paid for itself in less than a month. A second Buick-bodied Goose came two months later with five more goslings to follow, all of which employed cast-aluminum, Pierce-Arrow bodies.

To help keep motors cool, these piston-engined creations often ran with open hood panels, which flapped like wings at speed. The vehicles appeared to waddle on the ill-maintained RGS tracks and to some listeners, the original horns sounded like a goose with gas. The railroad originally referred to their creations as “motors,” but it didn’t take long for folks to bestow them with their fowl moniker.

The RGS made modifications to the Geese over their two-decade life. They replaced engines, added air brakes and resprayed their creations with longer-lasting aluminum paint. In the late ‘40s, Geese #3, #4 and #5 had their Pierce-Arrow cabs replaced with war surplus bus bodies.

After the RGS lost its mail contract in 1950, they cut windows into the boxcars, installed seats salvaged from Denver streetcars and tried to operate as a tourist train. Few folks came and the railroad folded in 1952. The Geese became orphans.

A faithful reproduction of Galloping Goose #1, which had been scrapped for parts in the ‘30s, can be seen at the Ridgway Railroad Museum.

Goose #2, which originally went to Alamosa, now nests at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden. Knott’s Berry Farm bought Goose #3 for their California amusement park.

A restored Goose #4 sits in downtown Telluride, and Goose #5 fronts the Galloping Goose Museum in Dolores.

Geese #6 and #7, which were originally used by scrappers to tear up the tracks, have also found a home at the Colorado Railroad Museum.

“Seven was in very sad condition when we got it and #6 was, too,” explains museum volunteer Al Blount. “Both engines were completely shot. We found three 1956 Chevy six-cylinder engines and got two of them to work. One is in Goose #7 and the other in #6.”

A retired global nuclear service specialist, Blount saw his first Goose in the late ‘40s on a Dolores River fishing trip. He didn’t get to ride in one back then, and when he started volunteering at the museum in 2002, none of their three Geese were operational. Blount recruited volunteers and personally took on the Goose restoration project. By 2008, they had all three running.

“Some parts we had to manufacture ourselves,” he recounts. “You can’t go down to a Pierce-Arrow dealer and buy something. You have to make quite a bit.”

The upholstery in Goose #7 was unrecognizably rotten, but Blount discovered a usable sample of the original hidden behind some wood. He found a near match, and using 14½ yards of fabric, he personally sewed the replacement upholstery himself.

“It took a while to do it. I would have to sew something at home, come down and see how it fit and then go back and make alterations.”

While the upholstery is close to the original, the volunteers had a little fun with other parts of their restoration efforts. The dashboard of Goose #6, for example, appears to hold an aircraft air speed indicator and an altimeter.

“They’re nothing but pieces of paper glued on the dash,” laughs Blount. “Our Geese don’t fly that high.”

For those who would like to take a jaunt in a Goose, the Colorado Rail Museum frequently offers three-lap rides in Goose #7 around their 1/3rd of a mile circuit. For longer excursions, the Galloping Goose Historical Society in Dolores periodically runs Goose #5 down the scenic Durango & Silverton and Cumbres & Toltec tracks.

“Our Fall Color Special on the Cumbres & Toltec is pretty spectacular,” brags society president Lou Matis.

Like the driver of a bus, the motorman sits at the left front. There’s a clutch pedal and accelerator on the floor, a gear shift lever to the right and a rear-view mirror overhead. What’s missing is a steering wheel. The Goose boasts a five-speed transmission and a 140-horsepower, GMC straight-six engine capable of pulling its eight tons up four-percent mountain grades.

“It’s geared in such a way that the top speed on this is about 45 mph, but we’re limited to 20,” explains senior motorman Larry Spencer. “Above that we start to oscillate with the front section going one way and the back the other.”

Spencer, a retired Denver firefighter, developed a lifelong fascination of railroading, especially narrow gauge railroading. On family vacations to Ouray, his father and brother often explored the Rio Grande Southern railroad grades, which had only been abandoned a few years.

“In 1999, a good friend of mine belonged to the Galloping Goose Historical Society and asked if I would like to come down for a ride. I got hooked,” he recounts. “Since then, I’ve done maintenance, learned to drive and been a motorman for about eight years now. I’ve driven all of the existing Geese except Knott’s Berry Farm’s #3. They wouldn’t let me because I wasn’t an employee. I wanted them to put me on the payroll for ten minutes, but they had very strict rules.”

Running with doors open and no glass in back, passengers hear the pounding of the engine, the whine of the transmission and the clacking of wheels on rails. Whistles blow and bells ring at every roadway crossing. Cars stop and people stand beside the tracks, waving and taking photos.

It doesn’t look like a train. It doesn’t sound like a train. The surprised looks on faces suggest most probably have never seen a Goose galloping down the rails.

[Story originally appeared in the September-October 2016 issue of Colorado Life magazine]