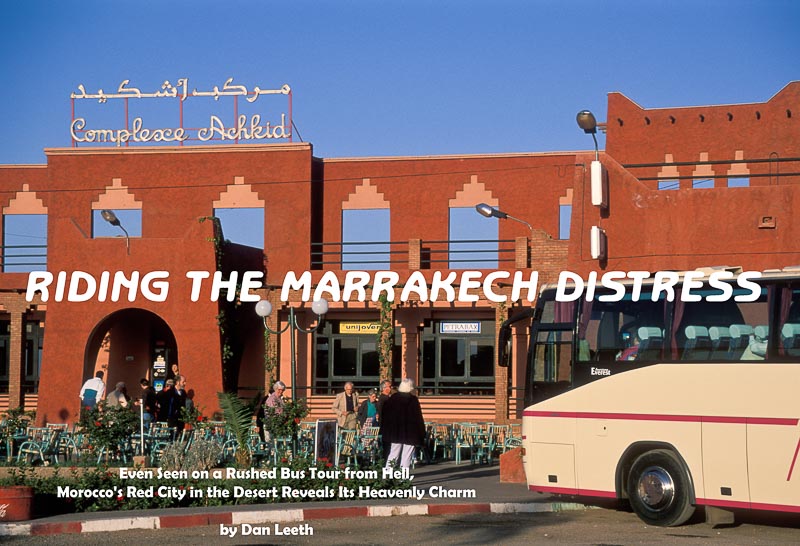

Over the years, I’ve taken many well organized motor coach tours. This was not one of them.

It began in Casablanca, Morocco, where I had a day to spare. Considering alternatives for passing the time, I ended up choosing an all-day tour to Marrakech. It would not allow much opportunity for exploration, but at least I would get a taste of Morocco’s red city in the desert.

The trip departed in predawn darkness. Bleary-eyed and caffeine-deprived, I stumbled aboard the idling bus. Grabbing a pair of empty seats near the back, I curled feline-like into a dozing, semicomatose ball. I failed to notice that a speaker hung immediately overhead.

“Nice to meet you all,” an amplified voice boomed inches from my ear. “My name is Mohammed. I’m your guide.”

Perhaps in his 40s, Mohammed stood six feet tall, sported a bushy mustache and wore a blue sharkskin suit. Like a hyperactive child, he yacked nonstop for the entire four-hour drive to Marrakech. Although we mostly heard about his friends, siblings, home, education and pet dog, Mohammed did relate a bit about this North African homeland. We found out about meats in the local diet, received lessons on how to make couscous and learned that the average Moroccan consumes 80 pounds of sugar annually.

“That’s why our women are very fat,” the guide snickered.

Mohammed’s favorite subject was polygamy. Under Islamic law, he said that a man can have up to four wives. His neighbor, he boasted, has two spouses and 24 children. Twenty-three are boys.

“The daughter, of course, does all the work around the house.”

A passenger asked the guide how many wives he had. Mohammed stammered, then admitted he possessed but a single spouse.

“One wife is good,” the man rationalized. “Two wives is problem. Three wives, more problems. Four wives is war.”

While the guide bantered, I stared at the countryside flashing by. At first fields and farms lined both sides of the highway, but the cropland soon merged into desert. Unlike the dune-draped landscape depicted in “Lawrence of Arabia,” this part of the western Sahara looked more like Arizona with rolling hills, rock outcropping and barren mountains. Sheep and goats foraged among prickly pear cacti. The same spiny plants served as living fences around the isolated Berber home sites.

By midmorning, the salmon-pink buildings of Marrakech loomed into view. With its core dating back nearly a thousand years, the city presents a fascinating homogenization of old and new. Modern apartments stand near timeworn hovels, and Mercedes sedans share the pavement with donkey-drawn wagons. Passing columns of cars, carts and camels, we arrived at our first Marrakech attraction, the Ménara Gardens.

“I beg you to stay together in one group,” Mohammed pleaded. “If we lose somebody, it will take three days to get him back.”

The Ménara Gardens feature over 200 acres of olive orchards, flowers and shrubs, but we scarcely saw any of them. We came to view only the site’s 12th-century swimming pool.

“Quick. Out of the bus,” Mohammed prodded.

With the speed of a Florida recount, 38 passengers oozed from the coach. Marching armpit to armpit, we followed our leader toward a rectangular pond spacious enough to hold a quartet of football gridirons.

“Before the Moors invaded Spain,” Mohammed told us, “they needed to teach desert soldiers how to swim. So they built this big stone pool. Now I show you surprise.”

Our guide tossed bread into the opaque water. The chunks floated like marshmallows in a cup of chocolate.

“Watch!” Mohammed smiled.

Nothing happened.

“No. You watch.”

After a 90-second eternity, a foot-long carp surfaced. Like a junior version of jaws, it lunged at the drifting delicacy. Its piscine partners soon joined the fray. In one brief feeding frenzy, the morsel disappeared. The show was over.

“Everybody, back on the bus,” our drill sergeant ordered. “Hurry. We have other places to go.”

We continued to the Koutoubia Mosque. Also completed in the 12th century, this structure replaced an earlier mosque that occupied nearly the same spot. In an engineering snafu reminiscent of today, it turned out the original house of worship was misaligned with Mecca.

“Let’s go,” Mohammed commanded. “Five minutes to get beautiful picture.”

We dribbled out, dodged traffic and walked to where we could view the 220-foot-high minaret. When new, plaster and decoration covered the tower. Now weathered nude, its walls exposed pinkish sandstone underpinnings.

“Everybody get photo? Good. Now, back to the bus.”

Turning to leave, we ran straight into three men dressed in red sequined with polished brass cups. These were the famed water sellers of Marrakech. Historically, the vendors peddled precious liquid squirted from a bag. Now, they profit by posing for pictures. I removed my lens cap and reached for a few dollar bills.

“No time!” Mohammed shouted as he shooed them off.

The tour proceeded to the Bahia Palace built in the 1800s. Empty now, it was once home of the sultan’s vizier, or “prime minister” as Mohammed called him.We blitzed down passageways and through courtyards, gardens, pavilions and reception halls. Although now in need of restoration, the edifice with its carved and gilded Moorish ceilings, must have once looked more ornate than the Playboy Mansion.

Mohammed led us into the master quarters. With the fervor of the “National Enquirer,” he revealed how the former owner had four wives and dozens of concubines. Grinning, he explained how a bedroom band would play for each soiree, their backs discretely turned. It sounded like the legend of an Arab Hugh Hefner.

Our next stop was the Saadian Tombs, a necropolis dating back to 1557. Stone-covered graves lie in a quiet enclave shaded by trees, shrubs and rosemary hedges. Two pillared mausoleums extend beyond. In this, one of the most visited shrines in Marrakech, we spent 15 minutes.

“Now we go shopping!” Mohammed announced.

Our guide marched us down side streets and into an alley that doubled as the local urinal. Through an unmarked door, we walked into a rug shop.

“Good buys here,” Mohammed hyped. “Go sit.”

My cohorts and I dutifully planted ourselves on benches. While women distributed cups of mint tea, a master salesman and his assistants tossed rugs across the floor. The brew was sweet and the designs exquisite, but I wanted to meet people. When Mohammed looked away, I escaped.

In a small square behind the shop, five boys played with string-thrown tops. Two younger girls watched from an apartment doorway. I held up my camera, seeking permission to take their photograph. The older girl smiled, then started preening her sister’s hair for the picture.

The boys soon came over. The older one, a lad of about 10, showed me his soccer cards and told me the names of the players. At least I think that’s what he was saying. I didn’t understand a word, but that didn’t deter our conversation. I let the kids look through the camera. They giggled, excitedly hogging the viewfinder.

The tour spent more time in the rug shop than at all previous sites combined. Clearly, Mohammed wanted his commission maximized. I rejoined the group after the last passenger finished negotiating her purchase. Only when we finally departed did one man discover that his wife was missing.

“Don’t worry. We go to lunch now,” the guide blithely announced. “I know how to handle this problem.”

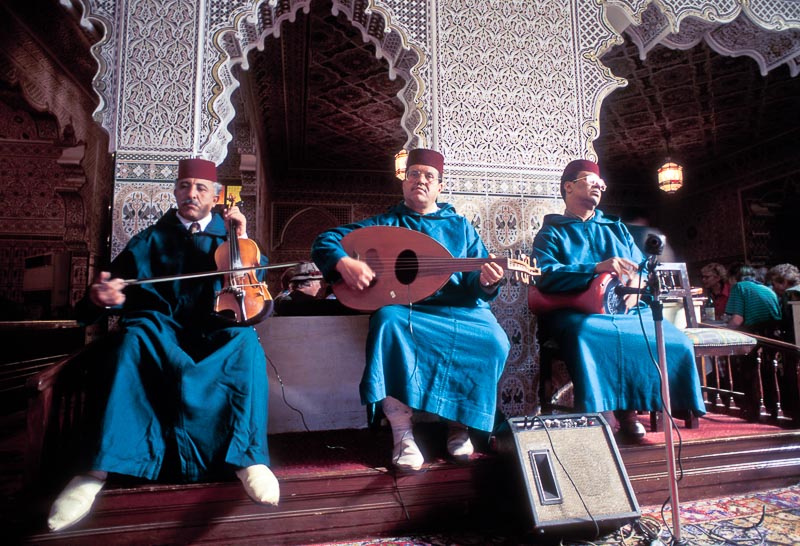

The husband and Mohammed’s local assistant went to find the wayward woman. The rest of us headed for a tourist restaurant. Inside, a trio of bored musicians played while we devoured salad, bread, chicken and couscous.

A busty belly dancer followed dessert. Practically popping from her top, she swiveled and gyrated to Moroccan riffs. Nearly every male had a camera flashing or camcorder rolling.

After lunch, we visited Place Djemaa el-Fna, the city’s bewitching central square. The place buzzed with life. Local men and women, garbed in full-length robes called djellabas, sauntered by. Scarves covered women’s heads, and veils often hid their faces. Capping the men, I saw more fezzes than at a Shriners’ convention.

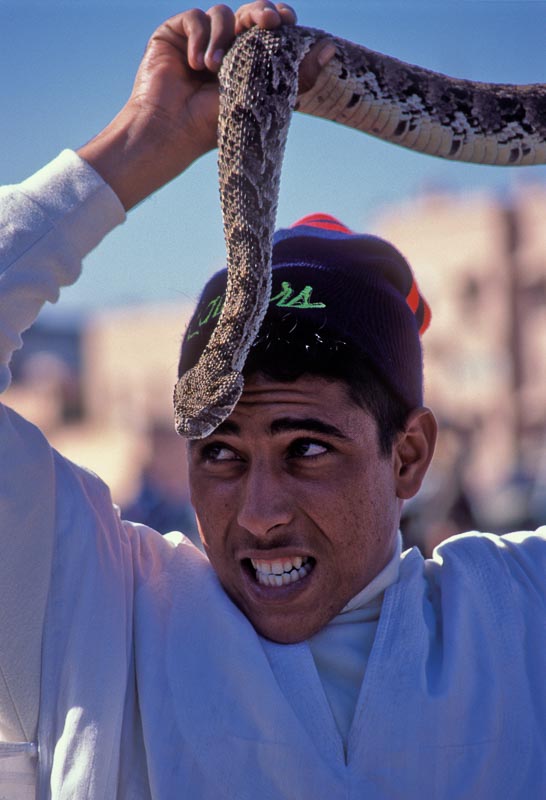

Snake charmers, monkey handlers, storytellers and scribes entertained on the cement. I watched one young man perform with cobras and a pit viper. He draped the reptiles over himself and kissed their fanged heads. The charmer hammed it up as I snapped gift photos for my snake-hating friends.

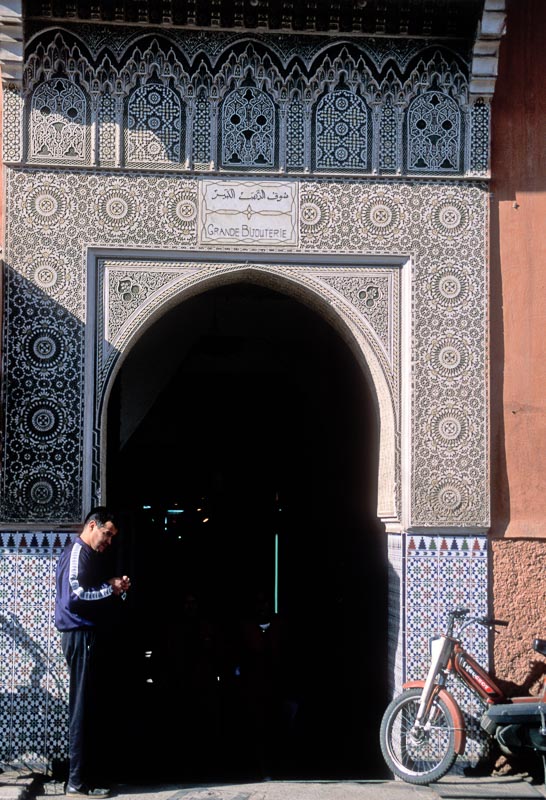

I wanted to wander farther and visit Marrakech’s famed souks, the city’s winding market alleyways crammed with merchants who boisterously hawk wares. But, Mohammed would not allow it. Twenty minutes after we arrived, the trail boss started herding us toward his motor coach corral.

“If we leave now, I can give you an extra half hour in a fine shop,” Mohammed offered. “Fixed price. No haggling.”

Reluctantly, I reboarded the bus. At least with Mohammed busy compounding commissions, I might still enjoy one final unguided encounter in the magic of Marrakech.