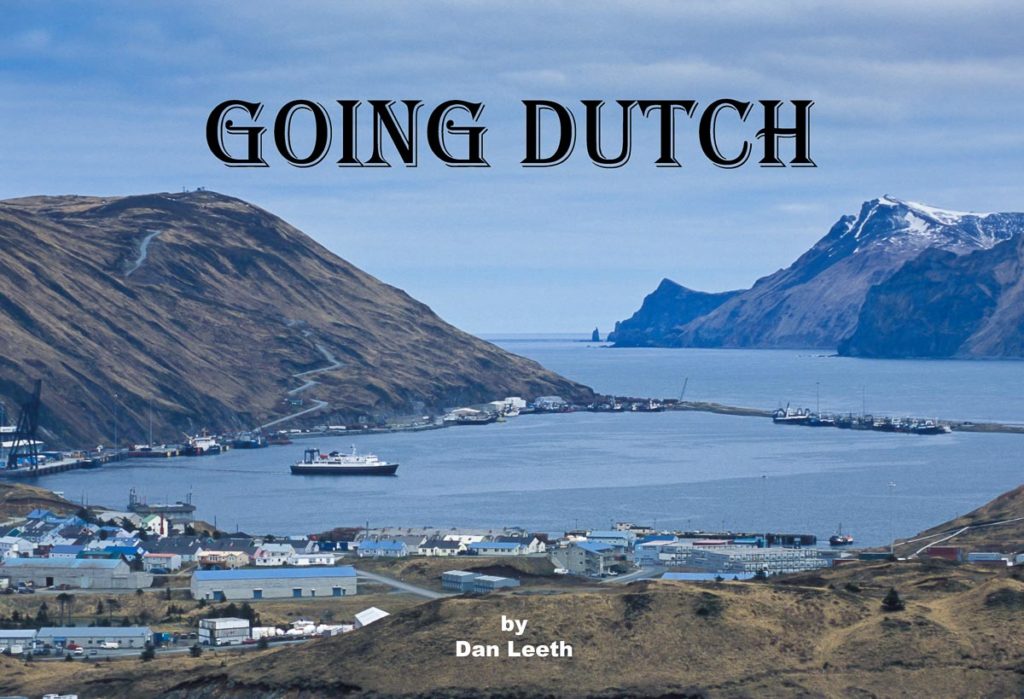

The Island may be Named Unalaska, but this Home of Discovery’s “Deadliest Catch” Offers a Real Slice of Genuine Alaska

Local lore claims that in the 1970s, Playboy declared the Elbow Room on Alaska’s Unalaska Island to be one of the roughest, most notorious bars in America.

Flush with cash, Bering Sea fishermen arrived looking for alcohol and trouble. They guzzled drinks six at a time and got into more fist fights than NHL players in a hockey game. When they weren’t punching bellies, patrons slid on them.

“They would pour pitchers of beer on the floor. Everybody would strip off their shirts and slide across, seeing who could glide the farthest,” reports Rick Kniaziowski. “The town’s matured a lot since then.”

It certainly has. Known to airlines and Deadliest Catch viewers as Dutch Harbor, Unalaska is the most populated port in the Aleutian Islands. Bigger than Maui and Molokai combined, the 4,000-inhabitant isle offers business-class lodging and restaurants, an anthropological museum, nine city parks, three national historic landmarks, a national wildlife refuge and a national historic area.

Today, it sports more churches than bars, its schools rank among the state’s best, and the notorious Elbow Room, now closed, serves booze and blows no more. Located closer to Russia than Juneau, Unalaska’s remote allure hooks us off-the-beaten-track travelers.

“We’re kind of like the UnCola,” explains Mayor Shirley Marquardt. “We don’t have trees, bears, snow, moose and things like that. What we’ve got is a real working Alaskan town that’s kind of on the fringes in the middle of the Bering Sea.”

The island’s un-name comes from the native “Ounalashka” meaning “near the peninsula,” and the harbor’s Dutch moniker reflects a time when a ship from the Netherlands anchored there. While “Dutch Harbor” remains commonly used, the official name for both the island and its town is “Unalaska.”

“Calling us Dutch Harbor is kind of like calling Seattle Elliott Bay,” complains Rick. “It’s only the name of the body of water.”

Getting here takes a bit of effort. A few cruise ships call, and Alaska Marine Highway ferries serve the island twice monthly from April through September. For most of us, however, it’s a three-hour, turboprop flight from Anchorage that gets us here.

Landing in Unalaska is like dropping onto an aircraft carrier. Water borders the runway on three sides, and a sawed-off hill rims the fourth. A pilot error here results in either a splash or splat. The Elbow Room may be closed, but the airport bar, I discover, is going strong.

I stay at the Grand Aleutian, a 112-room, three-story hotel. Its restaurant, I’m assured, offers the best (and only) Sunday brunch in town, and its gift shop carries crafts from Unalaska’s sister city of Petropavlovsk. I may not be able to see Russia from here, but at least I can buy souvenirs from there.

The town wraps around Iliuliuk Bay with part on Unalaska Island proper and part spilling onto a subsidiary isle. Connecting the two halves is the officially designated “Bridge to the Other Side.”

Downtown Unalaska has a last outpost of civilization look to it. Most homes seem modest with trailers, prefabs and refurbished World War II cabanas capping the real estate mix. The town sports a public library, community center, aquatic center and a staffed visitor center run by the optimistically named Convention and Visitors Bureau.

“Just how many conventions do you have here at the tail-end of Alaska?” I ask Rick, who served as executive director.

“Well, we hosted a state school board meeting once,” he smiles.

The biggest land-based employer is UniSea, which runs a highly automated pollack processing plant. Fillet from the white fish becomes sandwiches while the rest is ground into surimi that is used in imitation crab and fish sticks.

“There’s a one-in-ten chance that if it’s Alaskan pollack, it came from this plant,” Don Graves tells me on a tour. “McDonalds uses our pollack in their fish sandwiches as does Burger King.”

In addition to the commercial catch, sport fishing lures anglers to Unalaska. A replica of a 459-pound Pacific halibut hangs inside City Hall. Celebrities who have baited hooks here include Jimmy Buffett, who once performed an impromptu concert at the Elbow Room, allegedly without margarita belly slides.

At the end of downtown, a block from that infamous bar, sits the Church of the Holy Ascension. Started in 1825, this Russian Orthodox facility remains one of the oldest cruciform-style churches in the United States. Its icon collection dates back to the 16th century.

“The icons on the back wall, a set of 12, are called calendar icons,” explains local resident Susan Lynch. “There are only three full sets from this era in the whole world, and we have one of them.”

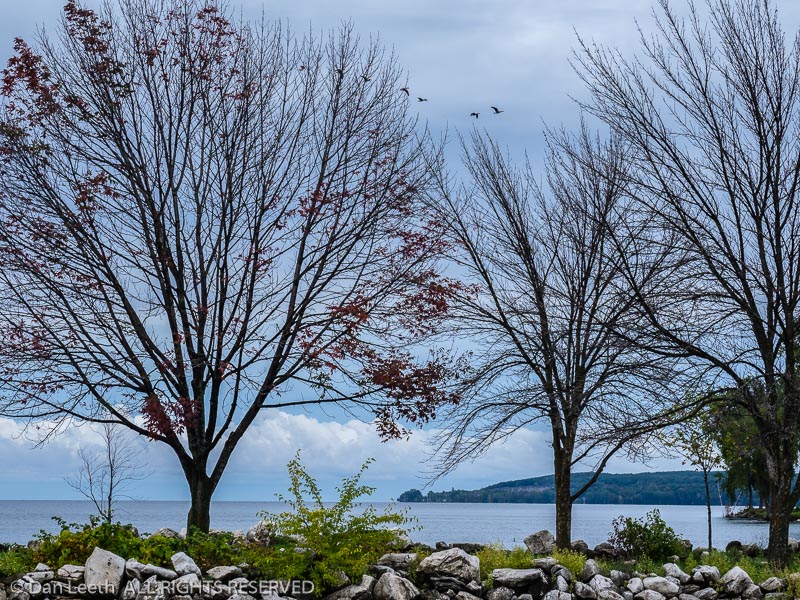

When it comes to trees, Unalaska stands as bare as Howie Mandel’s noggin. Hoping to make their fur-trading effort more self sufficient, the Russians planted Sitka spruce seedlings here in 1805. Six original trees still stand, becoming one of the few arboreal entries gracing the list of National Historic Landmarks.

Not far from my hotel sits the Museum of the Aleutians. It presents a collection of finely woven baskets, a 1778 drawing of an Unangan woman done by crewmember of Captain James Cook and a waterproof parka called a kamleika made from sea lion esophagus tissue. There’s also a 1940’s vintage ski, a model of the Coast Guard’s USS Bear and numerous World War II artifacts. One item, a Japanese soldier’s good-luck flag, has been returned to the family of the man whose fortune was battle ended.

“His widow had been told he was killed in the South Pacific,” explains Bobbie Lekanoff, owner of The Extra Mile Tours. “The Japanese kept it a secret that they were fighting in the Aleutians.”

The Visitor Center of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area displays information about the conflict and provides a mockup of a communications center with mannequins manning equipment. Bobbie reminds me that six months after Pearl Harbor, Japanese aircraft dropped their loads on Dutch Harbor.

“Right in front of us, you can see a dip in the ground that’s more green than everything else,” Bobbie points out. “That is a crater from where one of the bombs hit.”

Days after the attack, the Japanese invaded Kiska and Attu Islands further down the Aleutian chain. To stifle possible advances, allied forces stationed nearly 50,000 solders in Unalaska. Abandoned bunkers, pillboxes, ammo depots and gun mounts still surround town.

Bobbie’s tour mixes history with nature. By mid-July more than 160 species of flowering plants will carpet the mountains. Until then, bald eagles top the nature enthusiast’s interest list. With 878 spotted at a recent Christmas count, the national symbol can be seen perched everywhere around town. Bobbie monitors over 30 perennial nesting sites. The easiest nest to spot sits atop an unused construction crane in the middle of town.

“The first year they tried to build there, the sticks fell through,” she explains. “The following spring, a couple of local people climbed up and tied fishnet to the bottom. The eagles successfully completed their nest and have come back every year since.”

Another species that attracts birders to Unalaska is the rare whiskered auklet, whose range is limited to the Aleutians. To see them, I board a boat captained by wildlife biologist Tammy Peterson. We sail toward the Chelan Bank.

“The sea bottom comes up abruptly here, so there’s a big upwelling. It’s really nutrient rich, which means the bait fish are here along with whatever feeds on them,” she says. “It’s like a fast-food restaurant in the Bering Sea.”

We catch a pod of orcas breaching to the starboard and white-sided dolphins porpoising to the port. A short-tailed albatross glides overhead like a white, U2 spy plane. Tammy points out sooty shearwaters, tufted puffins and various species of gulls. Best of all, we spot numerous whiskered auklets. Our route back takes us past the airport.

“Nine years ago, my brother died,” Tammy reveals. “I got the phone call saying it was time, but I got stuck here for six days because of fog. He died before I could get off the island. That’s the drawback to living out here.”

Fortunately for me, the weather dawns fog-free my departure day. I head for the airport assured that not only will the plane will arrive and depart, but it will even be reasonably on-time. Unlike some fellow passengers, I don’t even feel a need to fortify myself at the bar.