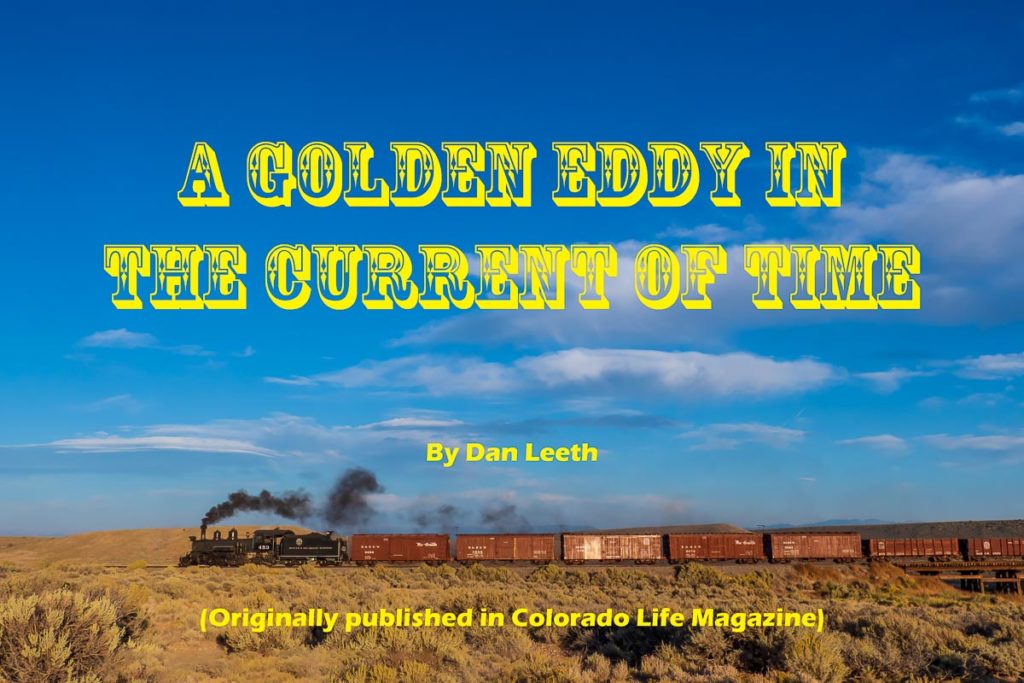

In the movie “Back to the Future,” a plutonium-powered DeLorean sportscar catapulted Michael J. Fox’s character, Marty McFly, 30 years into the past. Onboard the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, a coal-fired locomotive does a similar thing, transporting me and my fellow passengers a century and more back in time.

The longest and loftiest narrow-gauge route remaining in the country, the Cumbres & Toltec snakes back and forth along the state line between Antonito, Colorado, and Chama, New Mexico. Just as passengers have done since the train’s inception, we hear steam-driven pistons throb and wheels clack as cars sway down the tracks. Billowing smoke from the boiler scents the air with the heady aroma of burning coal. Over most of its 64-mile route, there are no paved roads, no powerlines and to the dismay of social-media addicted teens, no WiFi, internet or cell coverage. A panorama of wilderness-worthy scenery passes by in blissfully slow motion.

“It’s the past as far as the eye can see in any direction,” observes Cumbres & Toltec president John Bush. “It’s this eddy in the current of time.”

The route dates back to the early 1880s when the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad laid tracks linking Colorado’s capital with the mining mecca of Silverton. Rather than using standard gauge with rails spread 56½ inches apart, the Denver & Rio Grande placed its rails 36 inches apart so their trains could make tighter turns through sinuous mountain terrain. While many of the line’s narrow-gauge tracks were later converted to standard, the route between Antonito and Silverton remained unmodified. Today, the preserved sections from Durango to Silverton and Antonito to Chama offer scenic escapes into a bygone time.

Unlike its more northerly sister, which follows the Animas River through a lush canyon, the Cumbres & Toltec climbs through the mountains with sweeping views of hills and valleys along the way. Come fall, those slopes glisten with the Midas-touched leaves of autumn aspen.

“Riding this train is on my bucket list,” an excited passenger told me over breakfast at the vintage Steam Train Hotel in Antonito.

One-way Cumbres & Toltec journeys depart daily from either end. On this journey, I chose to head westbound from Antonito, which allowed me to watch herds of pronghorn dart across the San Luis Valley in the crisp light of morning. After the conductor punched my ticket, I left my reserved seat in a closed passenger car and headed for the open gondola where docents from Friends of the Cumbres & Toltec provide a commentary about what we’re seeing. As we approached a wooden trestle five miles from town, docent Bob Ross related a tale of its multiple monikers.

“There are two stories, the first of which I don’t believe,” he admitted. “Theoretically in 1880, they hung a guy named Ferguson off this trestle. That’s why they called it Hangman’s or Ferguson’s Trestle. The second story is definitely true. Willy Nelson made a movie out here in 1988 called ‘Where the Hell is That Gold.’ During the filming, they accidently burned the trestle down. So, they had to build us a new one. We now call it the Willie Nelson Trestle.”

A trackside sign soon revealed that we’d passed into New Mexico, the first 11 border crossings. We’d gained several hundred feet in altitude, and the sage and rabbitbrush of the San Luis Valley were giving way to piñon and juniper. Crossing back into Colorado, we rounded Whiplash Curve, a series of horseshoe-shaped loops needed to maintain an ascent angle of less than 1½ percent or roughly 80 vertical feet per linear mile.

As the piñon and juniper slowly surrendered territory to ponderosa pine, we were treated to sneak peeks of the autumn magnificence that lingered ahead. Trackside willows shimmered with gilded leaves. Nuggets of golden aspen began to salt slopes and line the tracks. A motherlode of 24-karat color sluiced down hillsides beyond.

The train stopped at the former railroad station of Sublette to take on water. Here, in seemingly the middle of nowhere, stands the home where a section foreman and his family once lived year-round. There were seven such section houses between Antonito and Chama, but only three remain. They have all been restored by the Friends along with trackside signs, whistle boards and mileage markers along the route.

“About 10 years ago we were out here painting the mileposts,” Ross told us. “All of a sudden, we heard something and looked up the hill. A mountain lion was staring down at us from maybe 50 feet away. Fortunately, the lion was not hungry, and we were able to get out of there without any problems.”

One of the advantages of narrow-gauge trackage was that many obstacles could be rounded and tunnels avoided. There are two exceptions on the Cumbres & Toltec. The first is the 342-foot-long Mud Tunnel, so named because it was bored through soft, loose volcanic material. It needed to be lined with heavy timbers to keep ceilings and walls from caving in. It, too, was featured in Willie Nelson’s movie. Fortunately, his pyro-crew avoided setting this one aflame.

We rounded a curve lined with freestanding rock pillars known as hoodoos. These monoliths cast eerie shadows in locomotive headlights at night, causing crewmen to christen it “Phantom Curve.”

Three miles later, we reached a bar hanging above the tracks with weighted ropes dangling down. Called a telltale, its purpose was to bonk the heads of brakemen walking atop boxcar roofs, warning them to duck. Rock Tunnel lay just ahead.

The 366-foot, curving shaft was blasted through solid igneous rock and needed no shoring. Immediately beyond, we enjoyed a quick glimpse into Toltec Gorge where sheer cliffs plummet 600 feet to the canyon’s floor. A sign asks passengers to not throw rocks as there may be fishermen below. Beyond stands a monument to James A. Garfield, America’s second president to be assassinated in office.

A bit past high noon, both the westbound and eastbound trains converge at Osier Station where a hot lunch, included in the ticket price, is served. Here, the railroad built a section house and depot, which the Friends have restored and opened to visitors.

While we stuff stomachs, wrench-wielding crewmen oiled bearings, checked brakes and attended to other maintenance needs. Unlike a living history museum where staff mimic tasks for show, crewmen on the Cumbres & Toltec perform the very same jobs their forebearers did to keep the trains running. Not only are the tasks the same, but many of the employees come from families who have worked on the railroad for generations, including our conductor’s son who’s a fifth-generation railway worker.

Back onboard, we crossed the 13-story-high Cascade Trestle, looped a hill, circled a meadow and chugged past a few summer homes. Here we got our first glimpse of Highway 17 connecting Antonito and Chama. Topping Tanglefoot Curve, we crossed the highway and stopped for water atop 10,015-foot Cumbres Pass where a depot, section house and other historic buildings still stand.

Cumbres Pass was a busy place in the old days. Because long, eastbound freight trains couldn’t ascend the four-percent grade from Chama, cars needed to be uncoupled in town and hauled up a dozen or so up at a time. When all the cars were atop Cumbres, they would be reconnected to a single locomotive and hauled down to Antonito and beyond. Even today, if more than eight cars are in the train, the railroad has to use a double-header arrangement up Cumbres with a pair of locomotives linked together to power the train to the top of the hill.

Departing Cumbres, we wound around Windy Point and began our steep descent toward Chama. The open valley beyond looked like a giant fruit bowl bursting with shades of lime green, lemon yellow and tangerine orange. The pavement winding below provided a silvery bow through this cornucopia of color. Where tracks recrossed the highway at the bottom stood a gaggle of camera-toting railroad groupies. Like paparazzi shadowing stars in a Technicolor blockbuster, they filled their memory cards with pictures of us as we chugged by.

Passing the Cresco Water Tank, we entered New Mexico for the final time. The land flattened out. I saw cattle grazing near the tracks, some of which looked as hairy as a Summer of Love hippie. They’re Asian yaks being bred for meat.

We passed the fake, movie-set water-tower pipe that the young Indy swung from in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.” No fewer than 15 movies have been filmed on the Cumbres & Toltec line.

After traversing a narrow section of the route, appropriately named the Narrows, we cross the Chama River on a steel-truss bridge, waved to campers at the Rio Chama RV Park and entered the rail yard where locomotives and scores of bygone freight cars line the sidings.

The present-day world awaited, but unlike Marty McFly, I didn’t need a silvery DeLorean to power me there. A thoroughly modern bus idled beside the depot, ready to whisk me and my fellow passengers back to the 21st century.

We’re off on what should be our final journey in our A-frame trailer.

Our first stop is in Chama, New Mexico, where we will be photographing the Cumbres & Toltec Railroad trains in brilliant fall color. Then it’s off to Homolovi State Park, Arizona, which lies near Petrified Forest National Park and the Painted Desert.

From there, we head north to Capitol Reef National Park, Utah. After a few pies there, we’ll be off to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon with a two-night stopover at Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park on the way.

From the Rim, it’s south to Dead Horse Ranch State Park in Arizona’s Verde Valley. After that, we head for two weeks at our favorite Arizona state park, Lost Dutchman, near Apache Junction.

Then it’s home by way of my favorite KOA in Bernalillo, New Mexico, which has a brew pub next door.

When we get back home, we’ll have a new Flagstaff Micro Lite box trailer waiting for us. Unlike our A-frame, it will have a big refrigerator/freezer, a bathroom with a Motel 6-worthy corner shower and holding tanks for wastewater. No more camping! We’ll become members of the mobile-motel crowd.

Dianne says no, we will still be “camping.” She just won’t have to crawl on the floor to get into the refrigerator and I won’t have to crawl over her comatose body to get out bed in the middle of the night.

One thing for sure – unlike other members of the mobile-motel crowd, we won’t be walking poodles and we won’t be sitting in front of a TV at night!

So, you might wonder, after six seasons and 400 nights spent camping in our trusty A-frame trailer, why will we soon be swapping it for a conventional box trailer. Let me explain.

It’s all my wife’s fault. Because the trailer folds down, the refrigerator is only of half height. And Dianne has bad knees. She can’t kneel. To get anything out of the fridge (like fetching another beer for her loving husband), she has to drop to her knees and crawl to the refrigerator door. “That’s getting old”, she says.

Then there’s the bed. It goes crossways across the back of the A-frame trailer. To get up in the middle of the night, he who sleeps on the back side has to crawl over she who sleeps on the front. “That, too, is getting old”, she says.

And then there’s the time it takes to get moving in the morning and setting up in the afternoon. Erecting the top takes 90 seconds. Moving boxes of food and luggage around (and everything else that is required to set things up) takes Dianne an hour or more. “That’s fine if we’re staying in one place for a longer period. It’s not great, however, for traveling when we’re staying in one spot for only a night” she says.

Yes, we might claim it’s because we need more room and storage space for our travels, but when all is said and done, the truth is that my loving wife just wants a new trailer.

We’ve spent the last week photographing the steam trains of the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad out of Chama, New Mexico, for an upcoming Colorado Life Magazine story. Today our photos went fowl as we began shooting recently arrived Galloping Goose Number 5.

For folks not aware of these birds on rails, let me explain. The Galloping Goose is a car-on-rails contraption cobbled together in the 1930s. It and a half-dozen of its nest mates kept the Rio Grande Southern Railroad (RGS) in business during the Great Depression and beyond.

Running from Durango to Ridgway, the RGS served the mining communities of Rico, Ophir and Telluride. The railroad was the most effective way to get mail, cargo and people to those remote communities, but with the economy sputtering, the cost of running steam locomotives over the mountains often exceeded income earned.

RGS employees in Ridgway came to the rescue. They converted an old car body into a rail-mobile sporting an auto frontend and a truck bed in back. Burning cheap gasoline and needing only one person to operate, their Frankensteinish creation immediately proved profitable. Six more were soon hatched.

Waddling down the tracks with engine covers flapping and horns sounding like goose toots, the machines quickly garnered their waterfowl nickname.

The galloping flock kept profits aloft for two decades. While other railroads experimented with gasoline-powered rail cars, none ever served so long in revenue service.

When the RGS finally lost their mail contract in 1949, they tried to operate as a scenic passenger line. The plan failed. The railroad folded and the Geese flew the coop.

Surprisingly, all but Goose #1 (which was scrapped in the ‘30s) remain today. Goose #4 rests in downtown Telluride and Goose #3 winged its way west to Knott’s Berry Farm in California. Geese #2, #6 and #7 all nest at the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden, and a faithful recreation of Goose #1 now occupies the Ridgway Railroad Museum.

Goose #5 resides at the Rio Grande Southern Railroad Museum in Dolores when it’s not on the road. For the rest of this week, it will be plying the Cumbres & Toltec tracks. Our ride, which will mark the third time we’ve ridden the Goose, comes tomorrow.

Galloping through glades of golden aspen should be pretty spectacular.