A Cruise to the Antarctic Circle Takes Voyagers Past the Last Land on Earth

Two nautical charts lie spread across the ship’s navigation table. Both indicate we are traversing “unsurveyed waters.” Concerned, the captain maintains a heading that overlaps a solitary line of depth soundings. Although a veteran of Antarctic waters, he has never before sailed this channel.

Visibility diminishes with dusk. Heavy snow begins to fall. The dime-sized flakes plaster windows on the bridge making it difficult to discern the icebergs that clog the channel. The floating obstacles, however, show clearly on radar. Images of ice paint the monitor with splotches of cold orange.

One massive, tangerine glob looms dead ahead. The scale registers a distance of three kilometers.

Then two.

At one kilometer, the captain breaks the silence with a whispered order. The helmsman flicks the wheel, and the ship begins angling.

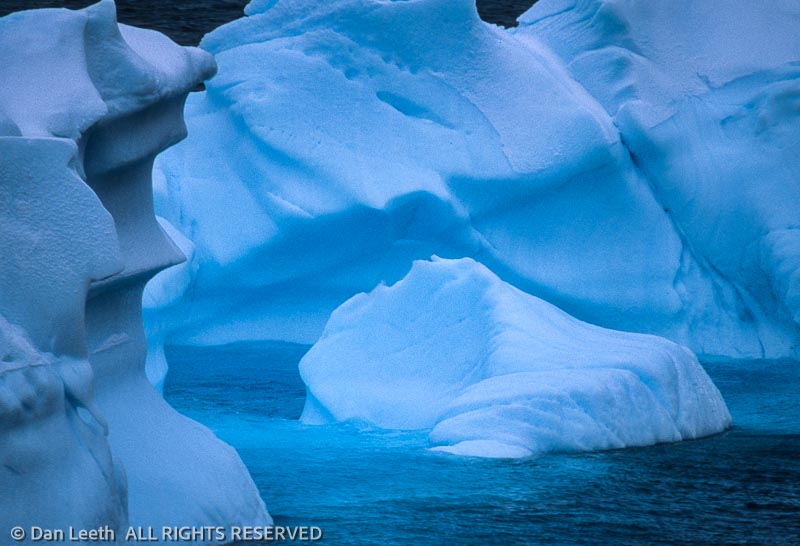

Through a shroud of fog and snow, a ghostly apparition reveals itself as a tabular iceberg, a form unique to the Southern Ocean. Its sheer sides rise a hundred feet to a top that stretches flat and wide as a Kansas homestead. Once again, I stand awestruck by the humbling magnitude of Antarctica.

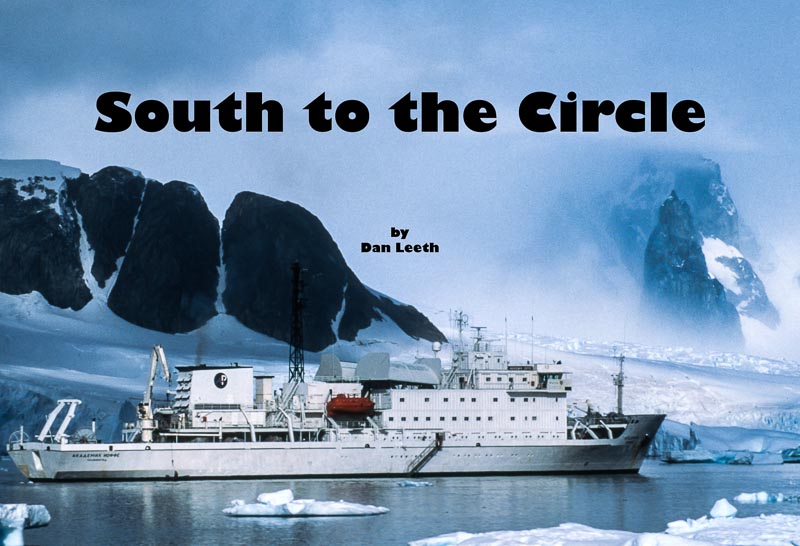

Our polar-class cruise vessel is bound for the Antarctic Circle, the dashed line that girds the bottom of the globe. The route there takes us past the most remote and uninhabited land on the planet.

Antarctica was not sighted until 1820. Another 79 years passed before anyone wintered on its surface. Explorers soon arrived in a deadly quest for the southern pole. Scientists followed. Until recently, the land’s only tourists were those who could afford five-figure fares. Now, prices have plummeted, and for about the cost of a Caribbean escapade, I booked a Marine Expeditions’ cruise to the seventh continent.

Antarctica is shaped like a manta ray with a curving tail. A 600-mile stretch of ocean separates the stinging end from the tip of South America. Through this gap known as the Drake Passage churn the roughest seas on earth. Negotiating the “Slobbering Jaws of Hell” is the true toll of admission to the last land on earth.

“Stow everything before you turn in,” the guides warn. “Also, securely latch cabin portholes.”

Leaving from Ushuaia, the Argentine city on Tierra del Fuego, the ship first navigates the placid waters of the Beagle Channel. Then, sometime in predawn darkness, we hit the open ocean.

For two days we do the Drake Shake, rocking and rolling through latitudes where no appreciable land tempers nautical might. Winds howl at near gale force. Waves explode over the bow, sending a shrapnel of ocean spray higher than my fourth deck window. Swells rise between 15 and 40 feet, their estimated size varying with the amount of sea sickness the observer is suffering.

“This is not too bad for the Drake,” a staff member assures me. “I’d say it is fairly typical.”

Our second day from South America, we enter the cold waters of the Southern Ocean. The following morning, I awaken to views of a coastal archipelago. Sedated by land, the seas have calmed to a gentle chop. Wisps of cloud float around mile-high summits. Angular ridges poke like chocolate shards from glacial frosting. Cracked, fissured, smooth and choppy, the ice flows in frozen slabs to the sea. It looks as though a range of Everests jut straight from ocean blue.

“This is like childbirth,” observes one motherly passenger. “Getting here is labor. Now we cradle the joy of parenthood.”

An unruly child, Antarctica is on average the coldest, windiest, highest and driest of the seven continents. Although its surface holds 70 percent of the world’s fresh water, the polar plateau receives about the same precipitation as Death Valley. Owned by no one, the land has no indigenous human population, and animals visit only briefly to molt and reproduce. It remains the only continent without a Holiday Inn.

In this region of extremes, sailing routes depend on weather, and shore landings are at the whim of wind and waves. Although the guides advise us to be flexible, our initial landfall comes on schedule.

We assemble on deck in predesignated groups. When mine is called, I join nine others in an inflatable Zodiac. The driver guns the outboard, and a quarter mile later, we bump dry land. With one step, I join the exclusive fraternity of people who have touched Antarctica.

Our first frat party is a black-tie affair hosted by a delegation of two-foot-tall penguins. Garbed in feathery tuxedos, they strut like aristocrats at a fund raiser. The majority of residents are chicks still covered in gray down, but a few adolescents are beginning to sprout head feathers. The hairdos make them look as bizarre as punk rockers at an opera.

At nearby Paradise Harbor, we take Zodiacs on a cruise through an inlet cul-de-sac that resembles an intimate version of Alaska’s Glacier Bay. Towering crags scrape the sky. Blankets of frozen ice drape the cirque in curtains of crystal blue. Miniature bergs reflect in mirror-still water.

We glide past Antarctic shags, which nest on a plunging cliff. Nearby, thick flocks of terns flutter in the air. Crabeater seals lounge on an ice floe. We approach, quietly sneaking photos like a boatload of paparazzi. The natives seem unfazed by our bold intrusion.

Outdoor temperatures along the peninsula typically hover around freezing, and a few layers of ski clothing provide comfortable warmth. One evening, we even enjoy an outdoor, deck-top barbecue. The chefs grill steaks, chicken, burgers and brats while the bartender mixes drinks with ice chipped from the remnants of a small berg. This is one picnic where brews stay cold, and ants definitely are not a problem.

Continuing south, we pass through the Lemaire Channel, a fjord-like corridor nicknamed “Kodak Gap.” Here, glistening mountains ascend from the ocean in postcard-perfect artistry. It looks as though we are sailing through the Alps after the Great Flood. The view is nearly identical to that seen by the first mariners who plied these waters. Apart from a handful of science bases, Antarctica remains virtually untrammeled by humankind.

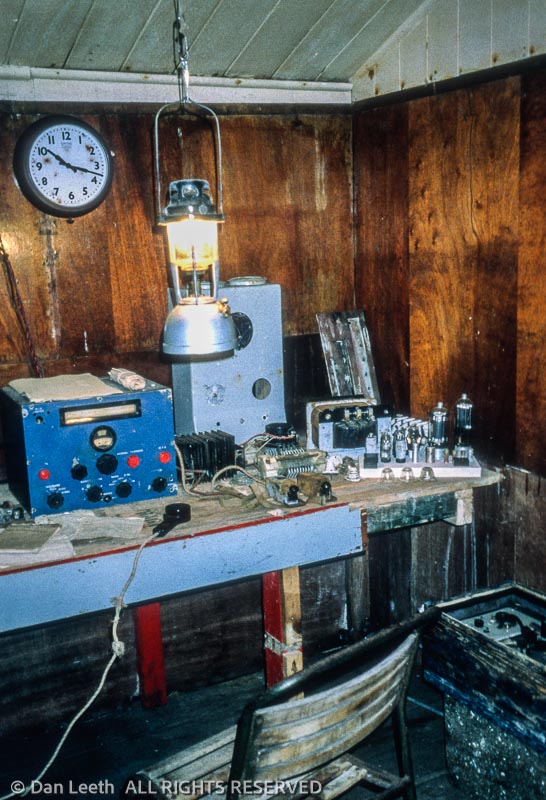

We visit one of the continent’s earlier research stations at Port Lockroy. Built by the British during World War II, it provided reconnaissance and weather data. The main hut, Bransfield House, remains the oldest British structure on the peninsula.

Now a historic site, Port Lockroy offers a glimpse of Antarctic life from a half-century past. The unpretentious buildings were made of wood, heat came from coal-burning stoves, and communication with the outside world was by vacuum-tube radio. Originally a crew of nine lived in spartan quarters. Now a pair of Antarctic veterans spend the austral summer refurbishing the facility. They also vend clothing, patches, stamps and postcards.

“We get over 40 tour boats each season,” says one of the pair. “The money we collect goes toward restoration.

While Antarctica is becoming a more popular destination, the continent still gets only about 10,000 visitors each year. Trip organizers have formed the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) to self-regulate tourism. Members pledge to travel safely, protect wildlife, respect protected and scientific areas and help keep earth’s last true wilderness pristine.

We stop at Petermann Island where the peninsula’s three species of penguins peacefully share an integrated neighborhood. Gentoos have snowy earmuff flashes that cross their heads from one eye to the other. Chinstraps sport black skull caps seemingly held in place by a thin line below their beaks. Adélies feature black noggins with their eyes ringed in white.

As we head south, we spy more wildlife from the ship’s bridge. Through its windows, I glimpse whales shooting plumes of vapor from blowholes. Above the surface, albatrosses soar on glider wings. Skuas and kelp gulls add to the aerial display.

When wildlife is absent, I admire the floating gallery of sculpted icebergs. Some look like Monument Valley monoliths. Others are honed and weathered like salt licks. Many glisten Clorox white, their ice still marbled with trapped air. The rest show pale blue, dense from years of glacial compression. Nearly all display a band of eerie luminescence that shimmers below the waterline like neon glowing beneath a low-rider.

The iceberg flotilla increases as we head farther south. I watch our progress on the Global Positioning System’s digital display. At a bleary-eyed 2:40 in the morning, the ship reaches 66 degrees, 30 minutes southern latitude. We cross the circle and enter the south polar world.

A few hours after dawn, we take Zodiacs to windswept Detaille Island. A British research station once operated here. Frequently frozen in, even the tenacious Brits gave up and left years ago. Their buildings remain.

Near the structures, Adélie penguins waddle up a snow slope, then toboggan down on their bellies. A hundred yards away, fur seals growl at each other. These animals have the disposition of a linebacker, are aggressive as Ken Starr and bear the teeth of Mike Tyson. Unlike other seals, they can run on their flippers. We maintain our distance.

One passenger found an old bicycle onboard, and he has it hauled ashore. A few of us take turns posing as polar pedalers atop the two-wheeler. For two hours, we goof-off, explore the island and view its wildlife. Finally, time comes to return. The crew hoists the Zodiacs aboard, and the ship turns north.

From his place on the bridge, the captain smiles. A look of relief seems to cover his face. The waters here may be unsurveyed, but he now brandishes the confidence of having sailed this way before.